“The first pattern is that forbearance toward the helpless has always been instrumental rather than absolute.” Historians Mark Grimsley and Clifford J Rogers (2002: xii), on treatment of civilians in war over time.

Much of the world’s attention has been focused on two recent tragedies: the Malaysia Airlines flight shot down over Ukraine and the civilian casualties in Gaza. In his Foreign Policy essay “The Slaughter of Innocents”, David Rothkopf couched these events within the concepts of ‘limited war’ and ‘collateral damage,’ writing:

From a purely political perspective, such tragedies, isolated though they may be, instantly dominate the narrative of a conflict because they speak to the heart of observers — whereas government speeches, Twitter feeds, and press releases seem too coldly rational and calculated, too soulless and self-interested. There are no arguments a political leader or a press officer can make that trump horror or anguish. There is no moral equation that offers a satisfactory calculus to enable us to accept the death of innocents as warranted.

I agree with much of this, except for one non-trivial point: tragedies involving civilian casualties are not that isolated, unfortunately. Not all incidents will be nearly as visible as the deaths of four young children playing football on a beach near a hotel filled with journalists, or a commercial airplane shot out of the sky. But they are all tragedies nonetheless. Civilian casualties are a feature of modern war, not a bug.

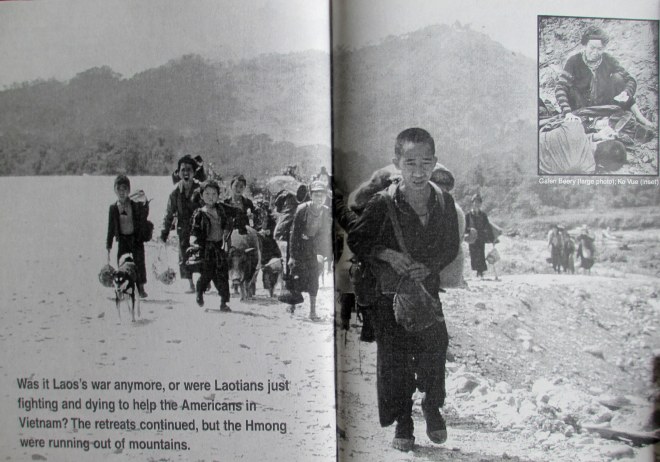

And this is not exactly a new pattern or feature of ‘limited war.’ Instead, nearly a century of data suggests that civilians, not soldiers, have suffered the brunt of war, experiencing 67% to 90% of casualties across various conflicts since WW2. And many more civilians suffer through forced displacement, along with its short- and long-term effects on health (Bradley 2014). Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised at these patterns, for the very simple reason that war is a sledgehammer, not a scalpel. It cannot easily excise some unwanted faction from a society without also cutting out several times more innocent lives. The real tragedy are not those ‘rare mistakes’ (which are not rare, really) that injure or kill civilians. It is the decision to go to war at all. Continue reading