I recently saw this France 24 video on the Hmong of French Guiana. I haven’t written about this much here on this blog, but I actually did some of my Ph.D. research with the Hmong in French Guiana years ago (here’s an article I published in the Hmong Studies Journal). It made me nostalgic to see the village again, as well as some familiar faces. My research assistant, KaLy Yang, and I were treated very well by the people in the two main Hmong villages (Cacao and Javouhey), and I think of the people there often.

French Guiana (or Guyane) is certainly one of the more unusual endpoints for the Hmong diaspora. As refugees from Laos, many Hmong resettled in the U.S., Australia, and France, after the Vietnam War, with lesser numbers in Canada, Germany, and Argentina (in fact, I met one Hmong man who originally resettled in Argentina before moving on to Javouhey). When people first learn there are refugees from Southeast Asia in the Amazon rainforest, it usually elicits a powerful reaction, either confusion or amazement. But then you learn the history, and it makes as much sense as any diasporic endpoint in a small, interconnected world where migration (voluntary or not) is common.

Some things have not changed. Farming appears as important as ever, and it seems the country is still largely dependent on Hmong agriculture. One man in the video, Joseph Lau, says that: “Here we have found our land. As a farmer, we couldn’t have hoped for better… My life is French Guiana.”

When I was there, most Hmong expressed being generally content with life in Guyane, including being self-sufficient and living in villages that were predominantly Hmong. This allowed them the ability to retain customs and language, though of course people learn French and assimilate to varying degrees. One woman in Javouhey told us that Guyanese life was close to “paradise,” since most Hmong were economically successful, owned their farms and homes, and lived in a tropical environment where their basic needs were met. In Cacao, some older men told us that when the Hmong first arrived in French Guiana, there were thirteen original elders. Nine of whom returned to France and had since passed away, while the four who remained in Cacao were still alive and active. This, they said, proved how healthy life was in French Guiana.

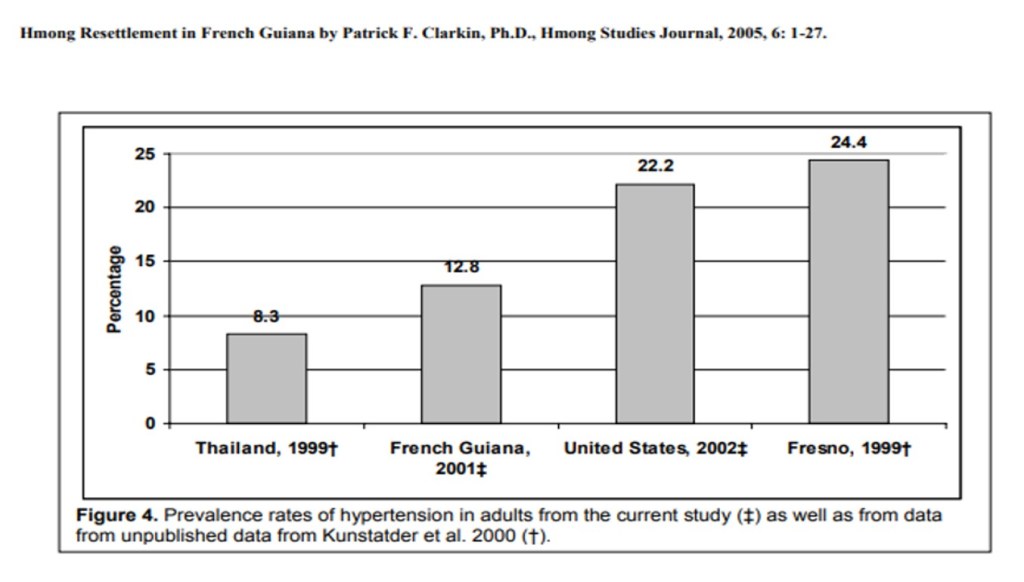

I also found some physical evidence to back up this claim by measuring people’s blood pressure. Hmong in Guyane had lower rates of hypertension than did their counterparts in the U.S., though they had higher rates than Hmong in Thailand (the Thai data were collected by Peter Kunstadter).

The perennial tensions between tradition and change still exist. A young Hmong woman in the video says that “I would like there to be things done here for young people. It’s not that I’m bored, but it could allow young people to develop in a certain way and have a bit of fun, just like everyone else.”

When I was there, I remember a young Hmong woman who had recently emigrated from France saying that while she liked life in Guyane overall, there were relatively few things to do with few restaurants or cinemas, etc. Many, but certainly not all, young Hmong adults were already emigrating to Cayenne, or France, or even the U.S. years ago. I imagine that trend won’t end anytime soon.

As far as experiments in migration go, the Hmong of Guyane are somewhat unique. With a bit of help they overcame a difficult history as refugees, adjusted well, became autonomous, and were able balance assimilation and cultural retention to a large degree on their own terms. I think it’s a pretty good story. If possible, future governments and refugee agencies might consider a similar model with other forcibly displaced populations.

A great trip down memory lane! (Which I share.) Kunstadter’s data on blood pressure is of course very dated now. I think the differences noted here are explained by physical activity and age. Traditional Hmong in the mountains do an enormous amount of walking — and working in their fields once there — while Hmong in urban environments have the same problems as any other ethnic group. Plus, perhaps even more significant, life length increases the nearer to a road and medical care — so many resettled refugees had a significant number of extra years compared to those who remained in the mountains. Extra years mean more time in front of the TV eating pizza and the onset of high blood pressure, diabetes etc. Gain some, lose some.

I agree, Robert. I think physical activity definitely played a role. In the two samples I had (the ones in the middle), the ages were pretty similar between them. I have since forgotten the ages in Peter Kunstadter’s samples were. You’re right that all things have tradeoffs. The exercise from a farming or mountain lifestyle likely benefits blood pressure, but the access to medical care in the US would as well.

Hope all is well in Vientiane.

Right, Patrick. All things indeed have trade-offs (although the negative is often not foreseen/considered when galloping towards what’s seen as positive). This perhaps counts for a great deal otherwise difficult to comprehend: e.g. normal, decent Germans and Austrians (hopefully) voted Hitler into power because of the full-employment policies (+’peoples’ car/highways) rather than the anti-semitic/anti-communist views expressed in Mein Kampf (although that was already a best-seller in German) — they got their increased prosperity but at a great price. (Similarities with Trumpism intentional.)

I looked at all the health issues in Hmong traditional life way back in the 1970s. I too can’t remember if Kunstadter took age into account, probably not as age is traditionally not accurately recorded other than ‘categories’ such as pubescent/married/grandparent; older/younger (but lifespan was also short in lowland societies at the time, making comparison difficult). Other researchers pointed to the free range pigs and dogs in villages as detrimental to health — as most villagers went barefoot and intestinal parasites (entering through bare soles) were very common. Some agencies advocated penning pigs and restricting the movement of dogs — but this meant human feces also went uncleared. The compromise avoiding the negative trade off was to provide simple foot-coverings (flip-flops) — along with de-worming pills.