“We have both a moral and ethical responsibility to protect all children and adolescents in our community. We cannot withhold information from children, adolescents, or adults, live in silence about this taboo subject and expect everything to turn out all right. We have tried ignorance and it does not work.”

– Joycelyn Elders, former Surgeon General, writing about human sexuality (2010: 249)

A few years ago, I began the “Humans are (Blank)-ogamous” series. I originally intended it to be only a few posts that would explore the roles that evolution and culture play in human sexual behavior. The inspiration for it was that several theorists over time had proposed that humans had evolved to be a number of things – monogamous, polygynous, serially monogamous, promiscuous, etc. I wondered how people could look at the same species and reach such different conclusions. Perhaps if I could read enough I might be able to find “the answer.”

From there, the series grew, blossoming into 20+ posts, citing over 200+ references (yes, I counted). I probably could have gotten at least a Master’s Thesis out of this. Anyway, those posts easily have been among the most read things on this site. That’s not because they are particularly brilliant. Rather, I think it’s because people are hungry for credible information and – despite how important the topic of human sexuality is – that can be hard to come by. Having those three magic letters “Ph.D.” after one’s name can help with internet search engine results, but a Ph.D. is no guarantee of being right. Far from it. All that means is that I went to school for a long time. I’m still in school, actually, so there’s always more to learn…

The series has been pretty well received by a number of people I admire, which feels pretty good I have to admit. They’ve been shared on social media, and some posts were even included on different university syllabi. In fact, I taught my own class on the subject last semester, and I think it went very well. When I re-read some of the earlier posts, there isn’t too much that I regret, (which is a good sign – sometimes when I reading my old stuff I sound like Sideshow Bob stepping on a rake).

With all that said, I think I think I’d like to wrap this up by taking the utilitarian approach. If I’m confident about anything that I wrote, and willing to put my money where my mouth is, then what would I emphasize to my students, friends, or (most importantly) to my own children? I’ll keep some of the lessons I’ve learned private, but here are a few:

- Love is real. There is an idea out there that romantic/ passionate love was somehow ‘invented’ by medieval bards, or somebody, somewhere. I think that’s a mistake. Perhaps that idea exists because the function of marriage has fluctuated over history, and at times its main purpose was more of a practical business transaction aimed at producing children, ensuring property rights, and cementing bonds between families. However, these aren’t the only components of marriage, and the evidence is very strong that passionate love exists across cultures, and has a pretty consistent biological profile. We didn’t invent it. Instead, because it is so powerful, it likely first evolved as a ‘commitment device’ as a mechanism for joint effort in raising offspring. However, even if that is how romantic love got its start, it didn’t have to stay tethered to its original function. Elderly people, who may have no interest in having children, can fall in love. So too can the very young, as well as a people of all sexualities. Original functions are not always synonymous with current ones.

- There are many ways to the top of the mountain. In the animal kingdom, prairie voles are often held up as paragons of monogamy. But even within this single species, there is variation – some prairie voles are quite promiscuous, and others less so. Evolutionarily, both are viable strategies, if they create offspring. If there is no single way to be a prairie vole, there is no single way to be a human either.

- Sex has many functions. For humans, sex is not solely about reproduction. Sex first evolved as a means of generating variation in offspring, but it did not stop there. Along the way, sex accumulated new functions, including pleasure (but not always), bonding, power, self-esteem. Sex can be many things, depending on context.

- Sex can be dangerous. I think social conservatives have a good point that sex can be harmful, so caution is not a bad thing. The emphasis is often on sexually transmitted diseases and unintended pregnancy, but there is also the potential for emotional harm, rejection, jealousy, etc. The trick, I think, is to remember that sex can be a mixed bag of emotions. Rather than being entirely ‘sex positive’ or ‘sex negative,’most societies, and most individuals, are to some degree sex ambivalent.

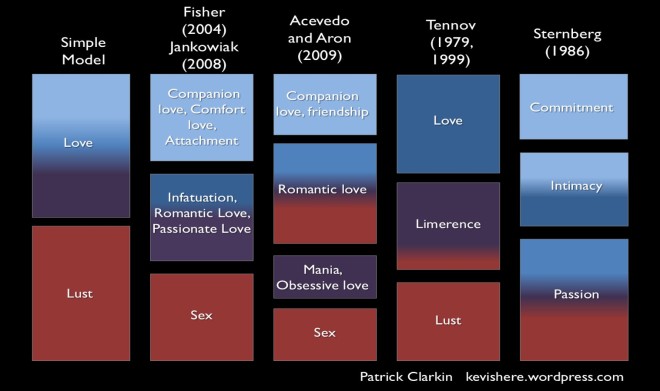

- We are complex, and sometimes contradictory. In Part 1, I quoted Robert Sapolsky, who once said that “We are not a classic pair-bonded species. We are not a polygamous, tournament species either. What we are, officially, is a tragically confused species.” Where does that confusion come from? In my readings, I noticed that different researchers seemed to arrive at a fairly similar model of erotic relationships, which is that they have three main components: sexual desire, passionate love (aka romantic love or infatuation), and companionate love (aka comfort love or attachment). One model included a fourth piece: mania or obsessive love (see above figure). These are among the more powerful of human motivations, but they do not always overlap perfectly, setting up the potential for flexibility as well as for conflict. One reason for this is that the different parts, whatever we want to call them – lust, romance, limerence, companionate love, friendship, commitment – are somewhat biologically distinct, and these can be arranged into different combinations and felt toward different people. Our flexibility as a species is one of our greatest strengths. It allows us to respond to circumstances and adjust to a range of environments, such as how we are omnivores capable of subsisting on a variety of diets. Similarly, human sexuality over time has responded to a variety of social circumstances, including polygyny, monogamy, polyandry (which is perhaps underappreciated), infidelity, uncommitted, non-monogamy, polyamory, etc.

- Culture matters. Undoubtedly, evolution has affected human sexual physiology and behavior, just as it has for every species. But humans have evolved to be behaviorally flexible, subject to the ideas and influences of our peers that can shift over time. What works in one time and place may not in another, and people have come up with a range of intimate relationships. According to the cultural anthropologist William Jankowiak, every culture is a work in progress, perpetually adjusting between two endpoints of prudery and licentiousness. As he said: “No culture is ever completely successful, or satisfied, with its synthesis or reconciliation of passionate, companion (or comfort) love, and sexual desire. Whether in the technological metropolis or in a simple farming community, there is tension between sexual mores and proscriptions governing the proper context for love (…) No culture gives equal weight to the use of sexual, the romantic, and the companionate metaphors. One passion is always regarded as a subset of the other.”

- Make room for variation. We have to reconcile two facts – all people belong to the same species and therefore have a consistent biology. At the same time, we are all unique. Therefore, we all vary in terms of our biology, including our sexuality. I think trying to shoe-horn everyone into a single sexuality is another mistake we often make. Unless you’re into shoe-horns. Jesse Bering once wrote that too often when people judge others’ sexuality they focus on what is “natural” (or what they think is natural), when instead we should focus on what is harmful. Subjective disgust, he argued, makes a poor moral argument because what seems repulsive to us may be another person’s paradise. For example, I may be repulsed by the smell of fried eggs (and I am), but I don’t want to ban fried eggs or stone to death people who love them. Instead, we should make room for fried egg lovers and a range of benign sexualities; otherwise we risk creating pain.

- All paths have trade-offs. In the words of Dr. Seuss, “Be sure when you step, step with care and great tact, and remember that life is a great balancing act.” Life is a series of choices and opportunity costs. In terms of sexuality, over a lifetime a person can have a range of sexual partners, or one, or none. We can have depth or breadth, or a little of both. You can marry young or late, have many children or none, etc. The point is that each choice we make necessarily means that we must forego other ones. You can’t have everything. Where would you put it?

- Perfect is the enemy of the good. In their book “Sex at Dawn,” Chris Ryan and Cacilda Jethá quoted Goethe, who once wrote that “Love is an ideal thing, marriage a real thing. A confusion of the real with the ideal never goes unpunished.” I think this is right. If the standard for a relationship is perfection, then disappointment becomes inevitable. This ties into the next point.

- Ignorance. Good information is preferable to no information. But no information is preferable to bad information. At least when there is no information, we are more apt to try to seek answers for ourselves. For example, Justin Garcia used the phrase “pluralistic ignorance” to describe what college students believed about sex and how comfortable their peers were with uncommitted sex. Similarly, if we are told that sex is just about reproduction or that long-term monogamy should come easily to everyone because it is the natural or default state of human beings, then this sets up certain expectations which may or may not be met. Long-term relationships carry a range of benefits – love, depth, stability, predictability, etc. But in all relationships over the long haul, challenges arise and personalities clash. It’s why weddings often carry the promise of “for better or for worse.” This is not meant to sound pessimistic, just a cautionary reminder that bad information can do harm.

- Kindness and vulnerability. Knowledge about evolution and anthropology will only get us so far. Of course, it’s not enough to know about the variety of human cultures and their marital practices, the mating habits of primates, or the neurobiology of romantic love. What probably matters most to us is our own happiness and the extent that we can achieve happiness without infringing upon others. Sex and love can be sources of happiness, but they can also leave us vulnerable if they are not reciprocated or if they become hard to find. I think the solution is kindness, not only to others, but also to ourselves, knowing our own desires and needs. A kinder society which understands that sexuality can be an area of intense vulnerability, and that we are all unique, can save a lot of people pain or even their lives. For my kids, we teach them that kindness comes first, more than intelligence, popularity, athleticism, attractiveness, or wealth. When kindness is lacking, the result is usually suffering. We have enough of that already in the world without adding to it.

Thanks to all for reading.

Reference

Elders MJ. 2010. Sex for health and pleasure throughout a lifetime. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 7(s5):248-9.

Series:

- Part 1. Introduction Link

- Part 2. Promiscuity Link

- Part 3. Promiscuity (Genetics) Link

- Part 4. Promiscuity (Anatomy/Physiology) Link

- Part 5. Pair-Bonding and Romantic Love Link

- Part 6. Many Intimate Relationships Link

- Part 7. Is It Possible to Love Two People? Link

- Part 8. Love and Suffering Link

- Part 9. Love Is an Evolutionary Compromise Link

- Part 10. Wondrously Complex Paleo-Sex Link

- Part 11. Sexaptation: The Many Functions of Sex Link

- Part 12. A Tripartite Conundrum Link

- Part 13. Is Monogamy ‘Natural’? Link

- Part 14. Paleo Hookups and Archaic Lovers Link

- Part 15. Lessons from Models of Sex and Love Link

- Related: Erotic Laundry Lists Link

- Related: Did Pair Bonds Evolve to Be Asymmetrical? Link

- Related: Evelyn’s Story Link

- Related: Flexible Love, at Any Age Link

- Related: Desire and Celibacy Link

- Related: Sapiosexuality & Our Behavioral Complexity Link

- Related: Sex Really Is Dangerous (and Other Adjectives) Link

- Related: Sex and Love in the Long-Run Link

Pingback: Testosterone Rex & “Humans Are (Blank)-ogamous” – Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Pingback: Blank-ogamous, Polyamory, & NPR – Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.