[Note (June 2020): I’m seeing an uptick in the number of views on this essay. Is there any reason? Since this site is a labor of love, I’m just curious how it is being used.]

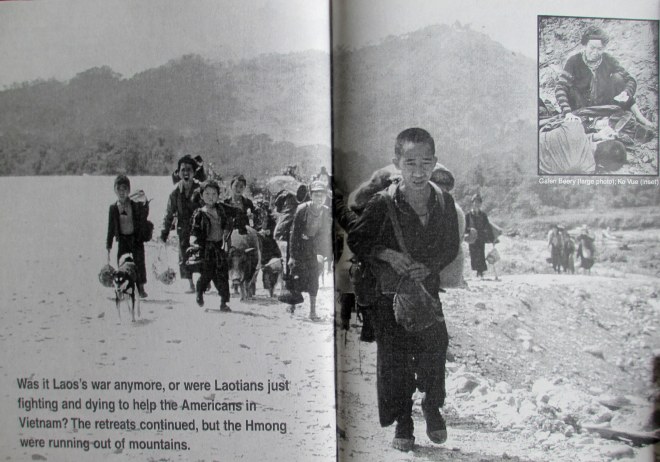

“In Houa Phanh and Xieng Khouang provinces, the war (in Laos) has reached into every home and forced every individual, down to the very youngest, to make the agonizing choice of flight or death.” (Yang 1993: 104)

“Those who suffered the most from the escalating conflict were populations living in the east of the country: overwhelmingly highland minorities, Lao Thoeng and particularly Lao Sung (Mien as well as Hmong), but also upland Tai, the Phuan of Xiang Khouang and the Phu-Tai of east central Laos.” (Stuart-Fox, 1997: 139)

“Military Region II (northeastern Laos) bore the brunt of the war for almost fifteen years. Nearly 80% of the refugee population in Laos originated in MR II, including the refugees on the Vientiane Plaine. Almost the entire population of Houa Phan (Sam Neua) and Xieng Khouang Provinces were gradually forced south into the Long Tieng, Ban Xon, Muang Cha crescent.” (USAID, 1976: 210)

A consistent feature of war is the harming of civilian lives. The extent of harm is not always easy to ascertain, but is sometimes quantified in the number of “excess deaths” that occur during a war. For example, Hagopian et al (2013) surveyed two thousand randomly selected households throughout Iraq, interviewing residents about their family members before and during the US-led invasion and occupation. They estimated that from March 2003-2011 approximately 405,000 deaths occurred as a result of the war, mostly from violence.

However, such studies always have limitations – recall bias, survivor bias (the dead cannot be interviewed), and logistics in surveying high violence areas – meaning that mortality estimates will never be perfect, and Hagopian et al. gave a range around their figure (a 95% uncertainty interval of 48,000 to 751,000 excess deaths). Whatever the exact number, which we will probably never know, we can still be confident that mortality rates increased during the war years.

The same challenges apply to all wars, including one that I have been interested in for a while – the Second Indochina War in Laos. The Australian historian Martin Stuart-Fox wrote that: “loss of life can only be guessed at, but 200,000 dead and twice that number of wounded would be a conservative estimate” (1997: 144). Mortality estimates for Laos are further complicated by the fact that it was one the least developed countries in Asia at the time of the war, likely with unreliable census data and other record keeping (though, for those who are interested, see the 1961 Joel Halpern “Laos Project Papers” from UCLA, which contain demographic and health statistics).