The introduction to this series can be found here.

Summary: There are many ways to put a human life together, including for sex and love. Each path has tradeoffs.

____________________________________________________________________

I thought I knew what love was. What did I know? – Don Henley, “Boys of Summer”

There are all kinds of love in this world, but never the same love twice. – F. Scott Fitzgerald

“Mom, love is love, whatever you are.” These words of wisdom came from Jackson, the 12 year-old son of actress Maria Bello, after she revealed to him that she had fallen in love with a woman. Bello’s essay, Coming Out as a Modern Family, appeared in last November’s New York Times, where she bravely reflected on her handful of past romantic relationships (mostly with men), her trepidation in revealing her evolving feelings on love, and the variety of meaningful relationships – platonic, familial, romantic – she had in her life.

In the most important sense, which is of course the sense that Jackson meant, love is love, irrespective of one’s sexuality, gender, or ethnicity. Studies from neurobiology reveal that people in the early stages of romantic love show consistent activation in specific brain regions (the ventral tegmental area and caudate) when viewing a photo of one’s partner. This was true for (1) men and women, (2) hetero- and homo-sexuals, and (3) American, British, and Chinese adults (Zeki and Romaya 2010; Xu et al. 2011). Not that Jackson needed it, because a person’s choices in love should be respected regardless of what neurobiology tells us, but he has science on his side.

However, in another sense, we also know that there are different kinds of love. Popular culture has tried to get at some of these nuances, giving us terms like furious love, puppy love, tainted love, ordinary love, everlasting love, stubborn love, cosmic love, and so on. Love is, arguably, one of the most overused words in English. We say we love our family, friends, country, books, pets, or maybe even our favorite food or work of art. But we don’t exactly get the same feeling from all of these, and they certainly differ from romantic love.

From a research perspective, Ellen Berscheid (2006) noted that the study of love is complicated by the fact that that it has no ready definition, despite its ubiquity. As she wrote: “to extract from the muddle of meanings of love a definition of what love really is, most scholars have grabbed their taxonomic broom and tried to tidy up the mess by sorting the myriad meanings of love into neat piles, each believed to reflect a variety of love” (p. 173).

How well do those models (or neat piles) match reality? Different researchers have come up with their own taxonomies, which more or less touch on the same themes, each with their own quirks. In biology, some taxonomists have a penchant for lumping similar organisms together. Others are quicker to see differences and are more apt to split them apart. This is also true for taxonomies of love. Comparing these models can provide a useful frame of reference, but this doesn’t necessarily mean that any of them perfectly capture the nature of love, or how it is “carved at the joints.”

Taxonomies of Love

Hendrick and Hendrick (1986) traced the modern history of taxonomies of love back to the work of John Alan Lee, and his six basic “love styles” (which overlap a lot with ancient Greek varieties of love). These included:

- eros, passionate love, with strong physical attraction and a “sense of inevitability of the relationship”

- ludus, an uncommitted, ‘game-playing’ love with a diverse set of partners

- storge, friendship love, “quiet and companionate”

- pragma, a logical, “shopping list” love; ex. looking for a good fit with family, a good parent

- mania, an obsessive dependent love, alternating between ecstasy and agony, which “usually does not end well”

- agape, an all-giving selfless love, such as during a partner’s illness

The Hendricks validated these by questionnaires given to students at two different universities, suggesting Lee’s varieties of love were more than mere constructs. In their view, people are capable of experiencing all of the above at different times, though individuals may gravitate to some styles more often than others.

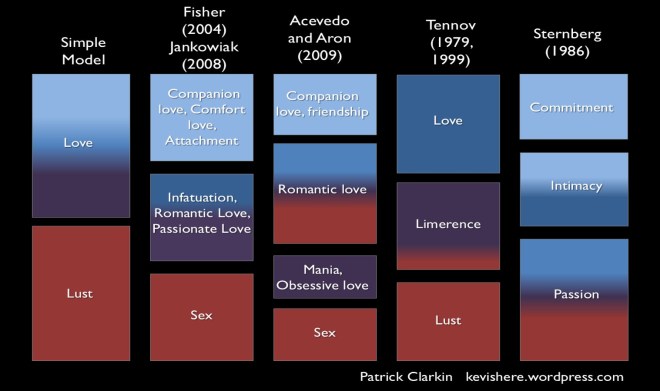

More recently, other researchers have described different taxonomies, which are more commonly cited in the scientific literature on love. These typically have fewer components – usually three or four – although vocabulary varies. By comparison, the simplest layperson model has two pieces: love and lust (an even simpler one might just be an all-encompassing term like ‘relationship’ or ‘marriage’ which hypothetically covers everything). Below is my attempt to align the varying models, coordinated by color. Overall, I think they are hinting at similar ideas, which is encouraging.

Sorting through some of the various taxonomies of love. Red = lust or sex drive. Purple = an obsessive quality, such as “intrusive thinking,” etc. Dark Blue = Romantic love. Light Blue = A calmer form of love (attachment, commitment, friendship). The list isn’t comprehensive, and in some categories I took some license with my reading of the author’s work, putting more than one element in a category. For example, Acevedo and Aron’s romantic love contains sex, romance, and a little obsession. But for them, obsession belongs mostly in its own category.

Elaine Hatfield and Richard Rapson (1993) identified three main components of erotic relationships: the sex drive, passionate love (aka romantic love or infatuation), and companionate love (aka comfort love or attachment). This is the basic model used by Helen Fisher (2004) and William Jankowiak (2008), which is interesting because Fisher is a biological anthropologist who looks at the neurobiology and evolution of love, while the other is a cultural anthropologist who studies the ways that different cultures try to balance the three components. That the two of them employ the same basic model, but from different perspectives suggests that it has merit.

‘Sex’ or lust may seem straightforward enough, but even this has many motivations behind it (Part 11). The differences between passionate love and companionate love were described in Part 5, but to quickly summarize: passionate love is much more intense and marked by ‘intrusive thinking,’ the idealization of one’s partner and a desire for emotional union even more than sex. It is also experienced earlier in a relationship, and its most intense phase appears to have a relatively short shelf-life, lasting for 1.5 to 3 years. Companionate love, by comparison, is not necessarily void of passion, but it is less intense, revolving more around long-term attachment, friendship, and deeply interwoven lives.

Again, the three parts are considered to be somewhat distinct entities with their own biological profiles. In my reading of things, the three overlap, and are never completely separate. For example, sex is a component of romantic love, and often companionate love. Certainly, one can have sexual desire without love, or love without sex (at least the companionate variety). However, romantic love (sometimes called ‘infatuation’) is built around both emotional union and sexual desire. As Jankowiak and Paladino (2008:15) wrote:

“Although sexual attraction is possible without infatuation, attraction always accompanies infatuation. In fact, sexual attraction is the very essence of infatuation.”

Helen Fisher and others have argued that even though romantic love tends to be more intense earlier in a relationship, it’s probably incorrect to think of the different types of love as stages. Romantic love does not ‘turn into’ companionate love any more than fat transforms into muscle. Instead, one can feel these things simultaneously or at different times over the course of a relationship, at varying intensities.

In their article “Does a long-term relationship kill romantic love?” Bianca Acevedo and Arthur Aron (2009) helpfully suggested that it’s a mistake to conflate the obsessive, intrusive thinking that often occurs early in a relationship with the entirety of romantic love. Instead, it is entirely possible to have enduring passion toward a partner over the long haul:

“We argue that romantic love—with intensity, engagement, and sexual interest— can last. Although it does not usually include the obsessional qualities of early stage love, it does not inevitably die out or at best turn into companionate love—a warm, less intense love, devoid of attraction and sexual desire. We suggest that romantic love in its later and early stages can share the qualities of intensity, engagement, and sexual liveliness.”

This deserves repeating because it is at odds with common caricatures of long-term relationships. In their book “The Myth of Monogamy,” David Barash and Judith Lipton (2002:187) asked, rhetorically, whether marriage is the grave of love. No, they replied; however, it is “the grave of savage love.” That’s not a completely fair assessment. Married people, on average, tend to have sex more regularly than do single people, though there is certainly variation (Kinsey Institute).

On the other hand, there is evidence that maintaining passion within a long-term relationship faces some challenges. To be sure, obsession dissipates, and this is reflected in fMRI scans and questionnaires of people who have been in relationships of more than 20 years (Acevedo et al 2012). Helen Fisher (2006) suggested that in the short run involuntary obsession can keep someone hyper-vigilant in looking for signs that their partner might lose interest. However, evolutionarily speaking, long-term obsession would be maladaptive in that it would be metabolically costly and it could perhaps even pull someone away from life’s other essential obligations (parenting, foraging, other relationships, etc). Therefore, it makes sense that it should have an expiration date.

The honeymoon period is also a real, somewhat short-lived phenomenon. In the early 1980s, Pepper Schwartz and Philip Blumstein looked as the lives of American couples, including sexual frequency. In new relationships, 67% of gay male couples had sex three or more times a week, compared to 45% of heterosexual couples, and 33% of lesbian couples. However, for couples who had been together for ten years or more, these numbers declined to 11%, 18%, and 1% respectively (Blumstein and Schwartz, 1983). There seems to be many possible factors involved here (aging, children, habituation to one’s partner), but it is hard to tease them apart because they are often happening at the same time.

The amount of time and energy that new parents must devote to young children is a particular challenge, and marital satisfaction often decreases around this time, as parents shift their priorities (Gray and Anderson, 2010). Peter B. Gray, who studies the evolution of fatherhood, jokingly wrote that having kids can have the destructive effect of a Godzilla on a couple’s sex life. However, kids are not the whole story. Childless couples face the same challenge of keeping a relationship fresh. Nor can lower frequency of sex be pinned only on aging. Unmarried straight couples in their 40’s, 50’s and 60’s have higher frequencies of regular sex than do married people at the same ages. Presumably, unmarried couples have not been together as long as the married ones, indicating that time spent together is a better predictor of sexual frequency than age alone. In one qualitative study of nineteen married women, over-familiarity with their spouse was cited as one of the core reasons for declining levels of desire (Sims and Meana 2010).

Percentage of heterosexual adults in the US reporting they had vaginal sex 2 or more times per week. Data from: http://www.kinseyinstitute.org/resources/FAQ.html#frequency

However, none of this means that passion must fade completely or inevitably. The study by Acevedo et al (2012) found that one of the more important brain regions involved in romantic love, the ventral tegmental area, became activated in people who had been married for more than twenty years when looking at a photo of their spouse. Finally, in one sample of 274 married people from across the US, 40.3% of those who had been together for more than ten years reported being “very intensely in love” (O’Leary et al 2011).

Limerence and Love

The manic, obsessive component of romantic love is roughly equivalent to what the late psychologist Dorothy Tennov called “limerence.” This term never quite took off in popular culture (my spellchecker doesn’t recognize it), but Tennov had a number of valuable insights from her research. In her view, limerence is akin to to what’s commonly called “being in love.” However, love is concerned primarily with the welfare and emotions of the other person. By contrast, what the limerent person desires above all is to have their feelings reciprocated by a specific other. While a limerent person can feel affection and concern for another, limerence is more of a desire to be loved rather than love itself, which is why she felt the need to coin a new word in order to distinguish between the two.

The third element in Tennov’s taxonomy, sex, is separate from limerence, though the two overlap:

“Limerence is not mere sexual attraction… Sex is neither essential nor, in itself, adequate to satisfy the limerent need. But sex is never entirely excluded in the limerent passion, either. Limerence is a desire for more than sex, and a desire in which the sexual act may represent the symbol of its highest achievement: reciprocation” (Tennov, 2009: 20).

While consummation is often imagined as occurring via sexual contact, at times she wrote it could be through holding hands, talking, a gaze, or even a sigh (1999:76). As Tennov put it, limerence is “first and foremost a condition of cognitive obsession,” an “all-consuming need” which is often viewed by those who know the limerent person as “more a form of insanity than a form of love” (p. 33 & 71). The insanity theme is not meant to be flippant about mental health, but it is also widespread in popular culture. As an example, one of the characters in Spike Jonze’s recent movie “Her” says that “Falling in love is a crazy thing to do. It’s kind of like a form of socially acceptable insanity.” In other parts of the world, Röttger-Rössler (2008: 172) found that several cultures – the Makassarese in Indonesia, the Taita in Kenya, parts of Japan and Sri Lanka and probably many others – viewed romantic love (i.e., limerence) primarily as a disruptive force, or even as a madness or illness requiring treatment.

However, Tennov was emphatic that each limerent person she interviewed was a rational, responsible, nonpathological individual in all other parts of life, with the possible exception of the limerence itself (p 89-90). She also wrote that the experience of limerence is often so powerful and transformative that her interviewees could often recall the moment it began, and here she used the French term coup de foudre (thunderbolt). And, when limerence is in full effect, Tennov noted that it would almost always eclipse other relationships. The parts are not all created equal.

It is also interesting that Tennov estimated that, based on her interviews, limerence most frequently lasted between 18 months to three years (p. 142), which is consistent with what other researchers found regarding the early stages of romantic love. However, as always, there is also a range of variation around this. In one extreme case, someone claimed to have felt a fifty-year unrequited yearning. Further, a substantial proportion of people found the experience is to be an unpleasant one. Half of the college students in Tennov’s sample reported being depressed over an unrequited limerent experience, while 17% had frequent suicidal thoughts (p. 149). To some extent, this reminds me of the story of 83-year old Evelyn, who told me that when she was a young woman she was “a walking skeleton for five years” over a man who didn’t return her love.

From an evolutionary sense, this seems terribly maladaptive. If reciprocation is the ultimate goal of the limerent person, then obsessing over one specific person for years or decades(!) without those feelings being returned is either a storybook example of dedicated romance, or a tremendous waste of time, energy, and probably a chance at happiness or even the opportunity to reproduce. Is the potential payoff worth it?

Cultural perceptions also matter. For some people, the conflation of limerence with love could mean that in order for it to be genuine, it has to be steadfast and unequivocal, even if the costs are total and even if there are plenty of other fish in the sea (or geladas on the plateau). In other words, the biology of limerence may be real, but –like everything else in human behavior– it can be reinforced or repressed by cultural interpretation.

Gelada baboons in Ethiopia (source: http://www.rockjumperbirding.com/wp-content/gallery/gallery-destination-ethiopia/geladas-by-markus-lilje.jpg).

Sternberg’s “Triangular Theory” of Love

Roger Sternberg’s (1986) “triangular theory” of love contained three interacting components: intimacy (emotional connection and closeness), passion (romance, physical attraction, and sexual consummation), and commitment (a decision to be with a particular partner for some duration). He described passion, intimacy, and commitment as being, hot, warm, and cold, respectively.

Sternberg’s three categories do not translate perfectly into, for example, Jankowiak’s or Fisher’s, at least not on their own. But what is nice about Sternberg’s model is that he emphasized how the parts can interact and create various combinations within a relationship. For example, a relationship that contained only intimacy without passion or commitment would be called “liking” (someone a lot). A relationship with commitment alone would be “empty love,” while one solely based on passion would be “infatuation” (this term is particularly variable among researchers). Passionate love comprises passion (obviously) and intimacy, while “companionate love” contains commitment and intimacy. For most people, the ultimate goal would be to have all three main components in order to achieve “consummate love,” though this was also difficult to maintain in the long-term.

Not to belabor these models, but the anthropologist Naomi Quinn (1982) found that in an American sample, “commitment” contained several consistent but variable meanings, including attachment, a promise, and dedication, as well as exclusivity. The point is that the main parts are not irreducible, and can be broken down further and further. One could also quibble that limerence and romantic love are a rather involuntary form of commitment, though Sternberg ’s idea of commitment pertained more to conscious choice.

Sternberg’s triangular theory of love, made of three main components: passion, intimacy, and commitment. These overlap and combine into different types of love.

Lessons from Taxonomies of Love

1. Vocabulary counts. Cultural narratives of love have a feedback effect that influence how individuals perceive their own emotional states. Emotions are probably pretty consistent across cultures and individuals (though always with some degree of variation), but some may be ‘hypocognized’ more than others, where individuals are not completely aware of them (Jankowiak and Paladino 2008: 9). Having a ready-made word or concept at one’s finger tips gives us something to tap into, but this may also lead us astray at times.

For example, Jonathan Haidt (2005) opined that Western cultures have inherited from the troubadours the myth of “true love,” which is passionate love which does not fade. Though most people recognize this only as a myth, if it is internalized, this can unconsciously set relationships up for unrealistic expectations and disappointment. As Haidt wrote, “if true love is defined as eternal passion, it is biologically impossible” (124). The heights of passionate love must come back down to earth. To Haidt, true love is committed companionate love, with some added levels of passion.

Jonathan Haidt’s hypothetical model of passionate love and companionate love in a (very) long-term relationship.

I think it’s probably above my paygrade to define “true love.” Instead, individuals and cultures will arrive at some definition that works best for them. And all the parts described above have unique properties, enticing in their own ways.

However, neologisms like Tennov’s ‘limerence’ have the advantage of shedding old baggage and expectations of polysemous words like love. Or, consider the phrase “new relationship energy,” commonly used within the polyamory community (Barker and Langdridge 2010). This seems to be touching on something similar to Fisher’s or Jankowiak’s romantic love or Tennov’s limerence, but with a more detached, descriptive terminology. My guess is that this simple rewording could encourage people to be more reflective about their emotions, to the extent that they can, to minimize the passive acceptance of existing cultural narratives of what love is ‘supposed’ to be.

2. The parts are separate and can be reshuffled. Historically and cross-culturally, people have come up with a variety of intimate relationships and mating structures (Part 6). Quite simply, there are many ways to put a human life together, including for love. One reason this is possible is that the different parts – sexual desire, romantic love, limerence, companionate love, friendship, commitment – are somewhat biologically distinct, and these can be arranged into different combinations and felt toward different people. For example, in one study of 349 university students and employees (mean age of 33 years), nearly all men (98%) and the vast majority of women (80%) reported having at least occasional sexual fantasies about someone other than their current partner, whom they presumably loved, indicating the near ubiquity of this experience (Hicks and Leitenberg 2001).

This ability to separate the parts affords our species behavioral flexibility, which is why human sexuality and mating defies simple description. This also sets up perennial tensions between romantic love, companionate love, and sexual desire across human societies, though the particular dynamics will depend on the individuals and the culture in question:

“The official ideal, and thus the preferred idiom of conversation, is the sexual, the romantic, or the companionship image. No culture gives equal weight to the use of sexual, romantic, or companionate metaphors. One passion is always regarded as a subset of the other. No matter how socially humane, politically enlightened, spiritually attuned, or technologically adapted, failure to integrate sex and love is the name of the game… To some degree dissatisfaction is everywhere: its dissonance sounds in all spheres of culture.” (Jankowiak and Paladino 2008: 1, emphasis added).

Those tensions play out in different ways across societies. One can imagine a woman in a polyandrous society who might feel more desire for one husband, or greater romantic attachment toward another, and possibly even limerent toward a paramour (see Tiwari, 2008 for examples from the highland Kinnauri in northern India). Sometimes this is intentional, sometimes opportunistic. Sometimes it’s socially sanctioned. Sometimes it’s forbidden. Sometimes it’s successful; at others it’s a disaster. Circumstances and context are essential. In their research in central Africa, Hewlett and Hewlett quoted an Ngandu man who described this ability to feel differently toward his two wives:

“I love my first wife the most, she is closest to my heart. She helps me and gives me food and respects me. We did not have children together; she was not able to. Now she does not menstruate, and we no longer have sex. I have sex with my second wife, to take care of the desire, but it is the first wife I love the most.” (2008: 52)

Jankowiak and Gerth found that in a small sample of 37 people from Las Vegas who loved two people concurrently, one partner was always identified as the companionate love (usually the first lover), the other being the passionate love, from which they tried to “form a cognitive whole of an ideal love.” However, no one had two equally companionate loves or two passionate loves. No one expressed being happy with their situation of loving two people, although these were all clandestine affairs, rather than consensual open relationships. By comparison, Jankowiak also looked at swinger communities (again, in Las Vegas), where sex with other people was openly or tacitly permitted. To swingers, the main tensions were between the competing desires of having sexual variety through a number of partners versus maintaining emotional intimacy via the uniqueness of the pair-bond. In this pursuit, they were fairly successful. However, 25% of the 80 participants revealed that the complexities of swinging had at one point threatened their relationship.

Many have recognized that when romantic love or limerence strikes, it often surpasses companionate love or even sexual desire, which is why swingers and many married people are wary of signs of it in their partner. The anthropologist Melvin Konner hypothesized that one of the early evolutionary functions of romantic love could have been not just for starting a new relationship, but for giving people the emotional push to leave an already established one. In short, romantic love can be just as disruptive as it is generative. This may be one reason Helen Fisher (1989) described the primary human reproductive strategy as “serial pairbonding,” as a passionate love can raise its head many times over the course of one’s life:

“We were built to love and love again. What joy this passion brings when you are single and starting out in life, divorced in middle age, or alone in your senior years. What confusion, what sorrow this chemistry can generate when you are married to someone you admire, then fall in love with someone else.” (Fisher 2004: 151-2)

However, even this is open to interpretation. The parts are not mystical forces that exist independent of the person. Rather, the individual can make decisions over what to do with the various erotic desires within (Barker and Langdridge 2010).

3. There is no perfect system. The holy grail of relationships seems to be achieving some combination of sexual fulfillment, romantic love, and attachment/ friendship, and making that last for years if not decades. However the formula varies by individual and culture. And, finding that balance does not always come easily, which often leaves us – as Sapolsky quipped – “tragically confused.” Because long-term relationships so commonly encounter bumps along the road, some have even pondered the ethics of enhancing or maintaining relationships with ingested neurochemicals, that is assuming one knew what the formula was (Savulescu & Sandberg 2008).

In the array of mating structures available, each comes with tradeoffs. In extreme cases, a life filled only with commitment, or even a series of exciting but short-lived passionate encounters, would be devoid of the other components. In reality, most people do not have extreme all-or-nothing scenarios. Rather, they have varying amounts of the three main components, which we may or may not be content with. And there are many ways to combine them in one relationship or several. For example, Terri Conley and colleagues took a critical look at the ways that monogamous and consenually non-monogamous relationships try to find their balance (Conley et al 2012). They argued that neither is inherently better or worse, though that depends on several factors.

Nor are the parts truly separate. Sex and love reinforce each other. O’Leary et al found that for couples who had been together for ten years or more, frequency of sexual intercourse was a highly significant predictor for those who reported being “intensely in love.” They don’t call it “making love” for nothing. However, an even better predictor was ‘physical affection’ (kissing, hugging, holding hands), including for older individuals.

“Of the individuals who reported no physical affection, not a single individual reported being intensely in love. Thus, some individuals, especially older individuals can feel intensely in love without intercourse in the past month, but a sine qua non for intense love to exist appears to be frequent affection” (p. 247).

Conclusion

Chris Ryan described humans as “sexual omnivores” in that we have the ability to go in many different directions in sex and love. Along similar lines, this series used the term “Blank-ogamous.” To our credit, dietary omnivory is one of our greatest assets in terms of being able to adapt to a range of environments, from tropical rainforests to circumpolar climates. But, like everything in evolution, there are costs even to flexibility. From a nutritional perspective, the omnivore’s dilemma is that by having a nearly unrestricted amount of choices, we can overemphasize one aspect of our nutritional needs at the expense of others. Hypothetically, you could eat almost nothing but chicken nuggets for fifteen years. It won’t make you healthy, but you could do it. This may also be true of our erotic lives. It’s about balancing competing desires, and people have come up with many different ways to do this. As the family therapist Esther Perel has said, “This is not a problem to be solved, but a paradox to be managed.”

The Korean samtaeguk symbolizes three swirling elements representing heaven, earth, and humanity. Like its more familiar cousin, the symbol of yin and yang, the samtaeguk implies that there is a perennial shifting dynamic among the three elements. For individuals and cultures, we are tasked with balancing the shifting dynamics of sexual desire, romantic love, and companionate love – and possibly other components as well – which may be lacking or in abundance at different times over the lifecourse.

References

Acevedo BP, Aron A. 2009. Does a long-term relationship kill romantic love? Review of General Psychology, 13, 59-65. Link

Acevedo BP Aron A, Fisher HE, Brown LL. 2012. Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012 Feb;7(2):145-59. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq092. Epub 2011 Jan 5. Link

Barash DP, Lipton JE. 2002. The Myth of Monogamy: Fidelity and Infidelity in Animals and People. New York: Holt. Link

Barker M, Langdridge D. 2010. Whatever happened to non-monogamies? Critical reflections on recent research and theory. Sexualities 13(6): 748-72. Link (removed)

Berscheid E. 2006. Searching for the meaning of “love,” In RJ Sternberg and K Weis (eds) The New Psychology of Love, pp. 171-183. New Haven: Yale Univ. Link

Conley TD, Ziegler A, Moors AC, Matsick JL, Valentine B. 2012. A critical examination of popular assumptions about the benefits and outcomes of monogamous relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 17(2): 124-41. Link

Fisher H. 1989. Evolution of human serial pairbonding. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 78: 331-54.

Fisher H. 2004. Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love.

Fisher H. 2006. The drive to love. The neural mechanism for mate selection, In RJ Sternberg and K Weis (eds) The New Psychology of Love, pp. 87-115. New Haven: Yale Univ. Link

Gray PB, Anderson KG. 2010. Fatherhood: Evolution and Human Paternal Behavior. Harvard.

Haidt J. 2005. The Happiness Hypothesis. Link

Hatfield E, Rapson RL. 1993. Love, Sex, and Intimacy: Their Psychology, Biology, and History. University of Hawaii. Link

Hendrick C, Hendrick S. 1986. A theory and method of love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50(2): 392-402. Link

Hewlett BL, Hewlett BS. 2008. A biocultural approach to sex, love, and intimacy in Central African foragers and farmers. In W Jankowiak (ed): Intimacies: Love & Sex Across Cultures. Pp. 37-64. Columbia Univ Press. Link

Hicks TV, Leitenberg H. 2001. Sexual fantasies about one’s partner versus someone else: Gender differences in incidence and frequency. The Journal of Sex Research 38(1): 43-50. Link

Jankowiak W. 2008. Intimacies: Love & Sex Across Cultures. Columbia Univ Press.

Jankowiak WR, Gerth H. n.d. Can you love more than one person at the same time? A research report. Link

Jankowiak WR, Paladino T. 2008. Desiring sex, longing for love. In W Jankowiak (ed): Intimacies: Love & Sex Across Cultures. Pp. 1-36. Columbia Univ Press.

O’Leary KD, Acevedo BP, Aron A, Huddy L, Mashek D. 2011. Is long-term love more than a rare phenomenon? If so, what are its correlates? Social Psychological and Personality Science3: 241-49.

Quinn N. 1982. “Commitment” in American marriage: a cultural analysis. American Ethnologist 9(4): 775-798.

Röttger-Rössler B. 2008. Voiced intimacies: verbalized experiences of love and sexuality in an Indonesian society. In W Jankowiak (ed): Intimacies: Love & Sex Across Cultures. Pp. 148-73. Columbia Univ Press.

Savulescu J, Sandberg A. 2008. Neuroenhancement of love and marriage: The chemicals between us. Neuroethics 1: 31-44.

Sims KE, Meana M. 2010. Why did passion wane? A qualitative study of married women’s attributions for declines in sexual desire. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 36(4): 360-80. Link

Sternberg RJ. 1986. A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review 93(2): 119-135. Link

Tennov D. 1999. Love and Limerence: the Experience of Being in Love. Scarborough House.

Tiwari G. 2008. Interplay of love, sex, and marriage in a polyandrous society in the high Himalayas of India. In W Jankowiak (ed): Intimacies: Love & Sex Across Cultures. Pp. 122-47. Columbia Univ Press.

Xu X, Aron A, Brown L, Cao G, Feng T, Weng X. 2011. Reward and motivation systems: A brain mapping study of early-stage intense romantic love in Chinese participants. Human Brain Mapping, 32(2), 249-257.

Zeki S, Romaya JP. 2010. The brain reaction to viewing faces of opposite- and same-sex romantic partners. PLoS One. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015802.Link

My graduate advisor mentioned several times how his classmate Hervé Varenne, who is a native of France and did his dissertation fieldwork on American kinship, was taken by the prominent role love takes in American family life.

I will definitely check this out.

It’s really neat to read about American society as seen by someone who finds it somewhat exotic.

I wouldn’t say that the book is theory-bound, but it might help to have a copy of Sherry Ortner’s “On Key Symbols” alongside as a crib.

Varenne also maintains a fun blog.

I particularly liked this part:

“Love is the domain par excellence of subjectivity, the unconscious, the nonscientific: it cannot, it must not, be possible to explain “why” so-and-so fell in love with so-and-so.”

There’s a lot of truth to that. From what I’ve read, most researchers say this may be an unanswerable question. But they still try. Perhaps there are too many variables, and the decision is too personal and idiosyncratic.

Hats off to you, Patrick. And of course to the Greeks for making a typology of love. It might be relevant to note that science has tried to explain love (and other feelings/passions) but so far has got about as far as the lady who I can’t remember who said “I know nothing about love , I’m married’. The long lasting ‘companionate’ love would seem to be the ideal of many (certainly for me), but I’m not sure how many people come close to it ~every time I think I glimpse it, it disappears. There is a basic fear of coming too close to another for too long. This might be evident in the popular Lao saying “A friend to eat with is easy to find, a friend to die with (for) doesn’t exist”. Saint-Exupery summed up a lot in 1939 (Terre des Hommes), “Life teaches that love is not gazing at each other but in looking together in the same direction”.

Thank you Robert. I tried to wrap my arms around the topic, but I think it’s too big. One of the articles I read started with a quote from Oscar Wilde:

“One should always be in love. That is the reason one should never marry.”

They then went on to say Wilde was wrong, and that the evidence shows that the two are not inherently incompatible (though the different types of love one feels may fluctuate over the long haul). It’s complicated.

Pingback: Morsels For The Mind – 04/04/2014 › Six Incredible Things Before Breakfast

Patrick. When you’re in love everything’s always complicated.

Fascinating. In some versions of the 12th century legend of “Tristan and Isolde,” the love potion’s effects “wane after three years.” This is pretty consistent with modern, scientific interpretations of limerence and romantic love. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tristan_and_Iseult#Legend

Reblogged this on Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D. and commented:

I’ve not had the time to write much here lately. Instead, I’m taking a shortcut by re-blogging an older post that I thought had at least some decent ideas/ lessons (and pretty graphs). I still need to wrap up this series, but am not sure exactly how.

Pingback: 2014 in Review | Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Pingback: Wrapping up the (Blank)-ogamous Series – Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Different types of love … are possible. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ptvWzJoS-fM