In graduate school, my advisor Mike Little recommended I take a class outside of the Anthropology Department, since our class offerings were slim that semester. He suggested I go over to Biology and sign up for David Murrish’s class “The Biology of Extreme Environments,” which explored how different species adapted to their worlds. Dr. Murrish kindly accepted me. On the first day of class, before getting into any subject matter, he asked the students for examples of extreme environments.

People suggested some of the ones you’re probably thinking of—deserts because of their heat, polar regions, the deep oceans, etc. I recall one student suggested outer space. I raised my hand and asked, “What about war?” Dr. Murrish smiled and said with a chuckle, “You anthropologists… always looking at the social side of things!”

Of course, biological anthropologists recognize that there is a natural world to which species adapt, which existed long before humans ever evolved roughly 300,000 years ago (Hublin et al 2017). Not everything about human biology can be attributed solely to “the social side of things.” In Mike Little’s classes we learned about his research with Quechua people in highland Peru and Turkana pastoralists in northwestern Kenya, and they how they adapted biologically to stressors in their respective environments: hypoxia, cold, aridity, seasonal rainfall (Leslie and Little, 1999; Little et al., 2013). But Dr. Murrish’s question that day made me think about other types of extreme environments that we create for ourselves, and war certainly applies.

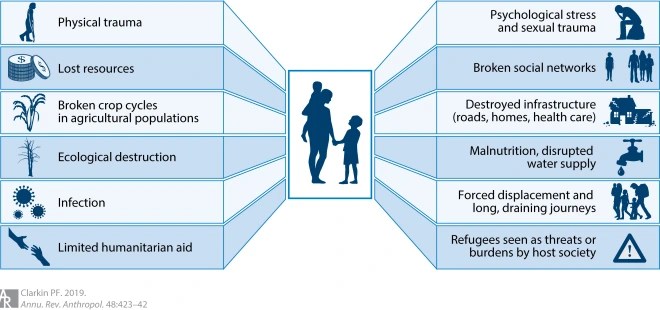

I didn’t get to explore war much further that semester, but the idea percolated. A couple of years later for my dissertation, I eventually explored how the Second Indochina War impacted the growth and body composition of Hmong refugees living in the US and French Guiana (Clarkin 2008). From there I thought about war as an environment in a general sense, including the various stressors they can create and the ways these things leave a mark on human biology and get “under the skin,” particularly among the very young who are still growing.

.

Continue reading