“We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.” – MLK

Are we all related? Yes. Now, act appropriately.

“We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools.” – MLK

Are we all related? Yes. Now, act appropriately.

Unbending rigor is the mate of death,

And wielding softness the company of life

Unbending soldiers get no victories;

The stiffest tree is readiest for the axe.

(Tao Te Ching: 76)

Early in life, our bodies are like unmolded clay, ready to be shaped by our experiences. For some of us, that matching process can create problems. If circumstances change, we could end up poorly adapted to our adult environment. A child born into harsh conditions, though, may have to take that risk in order to make it to adulthood at all.

The Hmong in French Guiana may be an example of this process. They are a fascinating population for many reasons, the most obvious being that they are there at all. A few dozen refugees from Laos first resettled in French Guiana in 1977, a few years after the Vietnam War, after they and the French government agreed that life in small, ethnically homogenous villages in a tropical environment was a better option than acculturating to the cities of Métropole France. The experiment paid off. Today, more than two thousand Hmong are farmers in the Amazonian jungle, producing most of the fruits and vegetables in the country. The result is a level of economic autonomy and cultural retention that is likely unique in the Southeast Asian refugee diaspora.

Scenes from Hmong villages in French Guiana. (Clockwise from top left: fields of Cacao, young men going on a hunting trip in Javouhey, swidden agriculture of Cacao, a street lined with farmers’ trucks in Javouhey.

“I’ll meet you further on up the road.”

Dragon’s blood tree on the island of Socotra, Yemen. Source.

I sometimes wish we could fast-forward through this messy period of human history. I imagine that our descendants will be embarrassed by how sectarian and insular we were. It will probably take generations, but it seems almost inevitable that the world will keep shrinking until it becomes the prevailing wisdom that all people share a common ancestry and that our commonalities outweigh our differences.

Yet, here we are. Ethno-nationalism is on the rise in Europe, with many people increasingly angered by the influx of Muslim refugees. In the United States, I.C.E. is rounding up and deporting people who have lived here for decades and who pose a threat to no one, including military veterans, a doctor, a mother of four children, and a college professor. President Trump infamously referred to several countries — including El Salvador, Haiti, and all of Africa — as “shitholes, and implied that people from those places should not be allowed to immigrate to the U.S. Left unspoken, this presumes that a country’s political or economic struggles are a reflection of the character of all of the people who live there.

A common refrain in these stories is the perception that outsiders are a threat, either in the form of direct violence or indirectly to “our way of life.” Again, in 2016 when Trump was still a candidate, he visited my home state of Rhode Island for a fund raiser and suggested that thousands of Syrian refugees were being resettled there without any screening and that they were akin to a Trojan horse:

“We can’t let this happen. But you have a lot of them resettling in Rhode Island. Just enjoy your — lock your doors, folks.”

At the time, there was one resettled family from Syria — a young couple and their three beautiful young children. The calculated wielding of fear as a weapon against five harmless human beings struck many people, including me, as cynical and reprehensible.

As for the threat to “our way of life,” a state senator from New Jersey named Mike Doherty epitomized this sentiment when he said that the U.S. should limit immigration from “non-European” nations that are not part of a “Judeo-Christian culture” because:

I recently saw the video below featuring the humanitarian organization No More Deaths, under the title “Is Giving Water to Migrants a Crime?” However, an alternative title could have been “Is Destroying Water Left for Migrants a Crime?” In the video, we see U.S. Border Agents in southern Arizona destroying water left by volunteers for migrants crossing via Mexico. We also learn that one of the group’s volunteers was arrested for “harboring two undocumented immigrants and giving them food, water and clean clothes.”

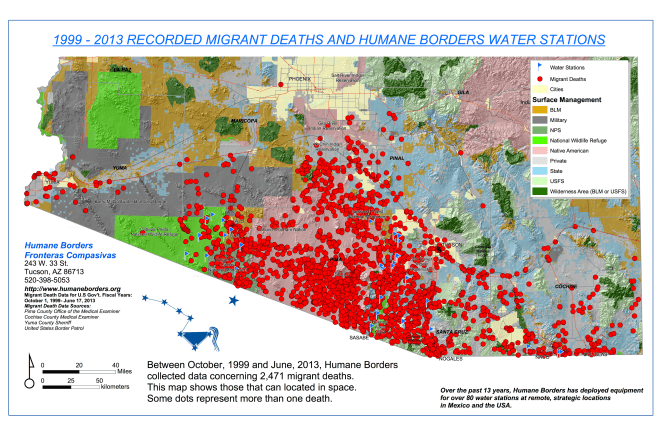

The area is home to the Sonoran Desert and is notorious for migrants dying from the heat and dehydration, from hypothermia (in winter), and from injuries and getting lost during the exhausting journey. Between 1999 and 2013, an estimated 2,400 people died in the area, according to the organization Human Borders. Certainly, more have died since. According to Betzi Younglas, a volunteer with the organization, “When the US began walling off the border cities and erecting a barrier right across Texas, they thought the danger of coming through here would deter the migrants. But they underestimated their desperation.”

Therefore, groups like “No More Deaths” are literally saving lives. Leaving aside the nuances of the debates about undocumented immigration, most (reasonable) people would agree that crossing an international border without proper paperwork should not be a death sentence (though here is an unreasonable example).

It occurred to me that border agents who damage food and water supplies left for migrants is something that would not be tolerated in war time. In 2016, referring to the war in Syria, U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon bluntly stated “Let me be clear: The use of starvation as a weapon of war is a war crime.” Of course, this applies to the deliberate deprivation of drinking water as well. According to Leslie Alan Horvitz and Christopher Catherwood’s book “The Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide” (2014: 406-7):

Do yourself a favor and watch this 6 minute short film on refugee children. You won’t regret it.

“You’ll always be special to me.”

Yesterday, it was reported that singer Dolores O’Riordan passed away unexpectedly at age 46. This one was a gut punch to me. I must have played The Cranberries‘ CD’s hundreds of times in college and graduate school, and I often had their songs on my playlist while traveling, including on a long, memorable bus ride through the mountains of Laos. Her voice and lyrics will be with me for a long time.

Somewhere between Phonsavan and Luang Prabang in northern Laos, 2009. I’ll long remember the breathtaking scenery, paired with the Cranberries’ music.

“The purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences.” – Ruth Benedict

“Imagine what seven billion people could accomplish if we all loved and respected each other.” – Anthony Douglas Williams

I just received notice from WordPress that it is the 8th anniversary for this site. To be honest, I have not been feeling too great about this site lately. Readership is down noticeably, and it has been harder to get the attention of my targeted audiences. I’ve even contemplated folding the tent.

Surely, part of that is me, as I’ve found it hard to maintain the volume of essays compared to prior years. Perhaps it’s merely the nature of today’s Internet. Eight years ago, there were fewer personal blogs and sites to compete for readers’ attention, and people seem to prefer shorter, more digestible, essays before moving on to the next item on their list. I understand. Time is finite, and we have things to do.

Earlier today there was a report that people in Hawaii received a warning that a missile was incoming. This turned out to be a false alarm, but for approximately twenty minutes many people believed a missile attack, possibly a nuclear one from North Korea, was imminent.

As with everything these days, the discussion online seemed to revolve around who was to blame. It appears that someone pushed the wrong button, causing anxiety and fear for many people. It could have been worse, had the wrong people panicked.

I immediately thought of Robert McNamara’s recollection of the Cuban Missile Crisis from the documentary “The Fog of War,” and the lessons he learned from that episode.

“If a bomb is deliberately dropped on a house or a vehicle on the grounds that a “suspected terrorist” is inside (note the frequent use of the word suspected as evidence of the uncertainty surrounding targets), the resulting deaths of women and children may not be intentional. But neither are they accidental. The proper description is “inevitable.”

-Howard Zinn, “War is not a solution for terrorism” The Boston Globe 2, 2006

UNICEF recently released a list of some of the most dangerous places for children to live. In various wars around the world, children have been killed, abducted, injured, raped, lost family members, and been forced into military service (“child soldiers”). In addition to the direct targeting of civilians, including children, war also creates indirect adversities including psychological stress, infections, and malnutrition. For example, in the ongoing conflict in Yemen, one million people have contracted the deadly diarrheal disease cholera, 600,000 of whom are children.

If you live in southern New England as I do, it can be hard to avoid the name Putnam. Putnam Cottage, Putnam Memorial State Park, Putnam Monument (Brooklyn), Putnam Monument (Hartford), Putnam Street and Putnam Pike in Rhode Island, Putnam House, Putnam County (several), Putnam Farm, Put’s Hill, Putnam Pond. My cousins grew up right near the town of Putnam Connecticut. There’s even a beer named after Putnam, brewed in Connecticut of course, and described as “full of flavor and unabashed amazingness.”

Traveling through the area, there are road signs for all of these memorials, dedicated the Revolutionary War general Israel Putnam, who was called “the provincial army’s most beloved officer” by historian Nathaniel Philbrick. Putnam was born in Massachusetts and lived most of his life in Connecticut, so it makes sense that any monuments of him would be found in this region. It’s interesting to note that many of these tributes were established years, decades, or even nearly two centuries after Putnam’s death in 1790. The town of Putnam, Connecticut was named in 1855. His monuments in Hartford and Brooklyn were dedicated in 1874 and 1888, respectively; the state Park was created in 1887, and his statue there was made in 1969.

Israel Putnam Monument in Brooklyn, Connecticut. Source.

The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins (1976) once told a story of a sociologist who studied equestrian statues in New York, noting the relationship between the number of feet the horse had in the air and the status of the rider. One foot in the air connoted something different than two feet or none. One observer argued that the study was complicated by the fact that people didn’t ride horses anymore. Because horses were largely obsolete, societies were less restrained in how they could consider and present them. To which another observer replied, “It’s true that people don’t ride horses anymore, but they still build statues.” Continue reading