If you ever get close to a human

And human behavior

Be ready, be ready to get confused

…

They’re terribly, terribly, terribly moody

…

And there is no map

And a compass wouldn’t help at all

(Bjork, Human Behaviour , 1993)

.

This semester I tried something new in my undergraduate class on anthropology and war. Briefly, the class has two parts: in the first half of the semester we explore cooperation, conflict, and war from an anthropological perspective. In the second half, we look at various ways that wars affect health and become embodied, or get “under the skin.”

When writing the syllabus back in early January, I thought about delving deeper into what’s going on in people’s minds when they feel violence is warranted, a topic I’ve written about before:

determining when violence (lethal and non-lethal) is morally justifiable can be a gray zone, with people positioning themselves on a continuum between completely nonviolent “doves” to hyper-aggressive “hawks.” While many people hold nonviolence as an ideal; living up to that ideal perfectly has proven difficult to almost impossible. The question is where people draw their line.

.

For the class exercise, I gave students a survey. On a scale of 0 to 100, I asked them to rate how justifiable it would be to use violence under 28 different scenarios. For a bit more background, I picked some scenarios that were hypothetical (ex. Gandhi’s famous example of using violence to “dispatch” a man in the act of committing mass murder with a sword), while others were based on real-world events. I did not tell students which scenarios were hypothetical or not ahead of time, but did so after compiling results, which they then discussed in groups. A few scenarios involved variations on a theme to find where people drew their lines. Some scenarios were about the behavior of other people, while others were about how students themselves might respond. And some involved lethal violence, others sub-lethal, and still others pertained to threats of violence (therefore, the numeric results aren’t all directly comparable).

Part of the inspiration for doing this exercise in the first place was me being dismayed by a range of violent current events (ex. Luigi Mangione; a man who shot children for throwing snowballs at his car; a student who stabbed people in a gender studies class they felt was too “woke”), and wondering about the subsurface mental machinery behind this behavior. Perhaps if we can raise this machinery up and into the light a bit, we might give ourselves a map and a compass and have a better handle on understanding ourselves. Ideally, we might even curtail violence slightly (a tall order, I know).

In previous semesters in this class, I’ve discussed ideas on “moral violence.” For example, as psychologist Tage Rai wrote, “most violence in the world is motivated by moral sentiments.” In our capacity as moral animals, we recognize others’ bad behavior and may sometimes feel they deserve punishment for their supposed moral failings, going beyond mere self-defense and into enforcement of social standards.

There is a tendency to see dehumanization as a major reason for violence, which has certainly been a motive in history. But the concept of moral violence suggests that people may harm others not necessarily because they think they are sub-human, but because they see them as bad humans who have failed morally in some way.

However, culture and human behavior being as pliable as they are, there is a lot of wiggle room around what behavior is considered immoral, and how justifiable violent punishment may be. To help distill this down a bit more, I used psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s six “moral foundations” as inspiration when compiling the survey. Those include: (1) Care/harm, (2) Fairness/cheating, (3) Loyalty to the group/betrayal, (4) Authority/subversion, (5) Sanctity/degradation, and (6) Liberty/oppression.

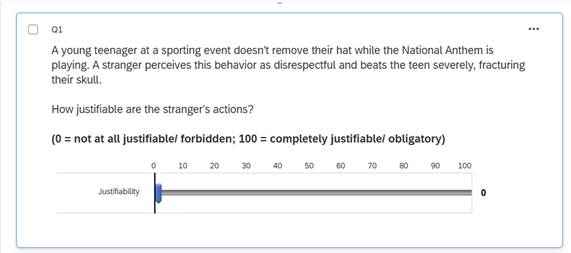

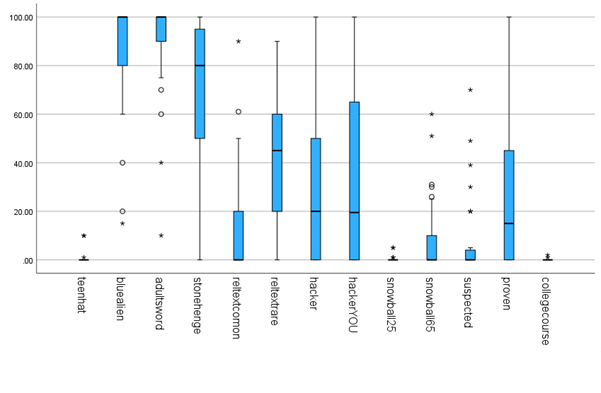

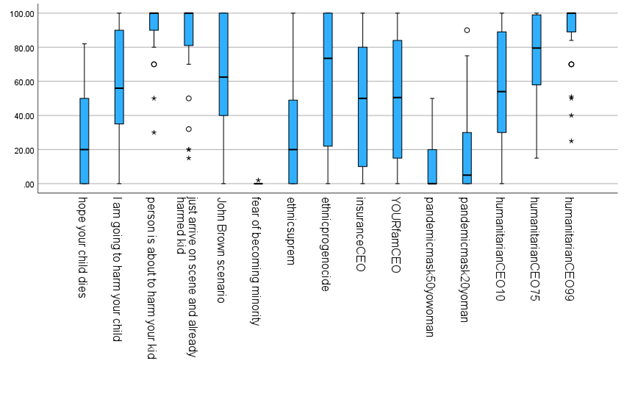

Here were the first 13 scenarios in the survey, followed by a boxplot of student results. Altogether, 34 students completed the survey and replies were anonymous.

(0 = not at all justifiable/ forbidden; 100 = completely justifiable/ obligatory)

1. A young teenager at a sporting event doesn’t remove their hat while the National Anthem is playing. A stranger perceives this behavior as disrespectful and beats the teen severely, fracturing their skull. How justifiable are the stranger’s actions?

2. A blue alien (along with some friends, an army, and some magic stones) promises to wipe out half of humanity. How justifiable is it to use violence to stop them?

3. An adult with a sword is seen running through a village using it to injure and kill dozens of people, with no signs of stopping. How justifiable is it to use violence to stop them?

4. Someone has placed several bombs around the Stonehenge monument in England. They say that this is because they don’t like the ancient religion it represents. Negotiations have failed. How justifiable is it to use violence to stop them?

5 & 6. A young adult is about to burn a common, mass produced copy of a text of the religion closest to your own personal upbringing (a Qur’an, Bible, Torah, Vedas, Sutras, etc.). (A) How justifiable is it to use violence to stop them? (B) What if it was a rare, original text hundreds or thousands of years old?

7 & 8. A hacker entered a university’s computer systems and erased all the credits and grades of a student. The university and police say there is nothing they can do to fix this, and the student must re-take every class. The student somehow learns the identity of the hacker. Along with some friends and relatives, they inflict severe physical harm on the hacker. (A) How justifiable were the student’s actions? (B) What if YOU were the student who was hacked?

9 & 10. On a city street, two 12-year old boys throw snowballs at a car that was driving 25 mph. The car is not damaged. The driver is unharmed, but startled and angry. They drive around the block to confront the boys and shoot the boys in the legs. (A) How justifiable are the driver’s actions? (B) What if the driver was on the highway, driving 65 mph, and the snowball caused the driver to crash?

11 & 12. Someone strongly suspects that their preferred political candidate lost because the election was rigged and stolen by corrupt officials. They decide to leave dozens of death threats on the officials’ voicemail. (A) How justifiable are the death threats? (B) What if there was incontrovertible proof that the election was in fact stolen?

13. Someone discovers that there is a college course that teaches subject matter that they strongly disagree with and that they believe conveys dangerous ideas. They enter the classroom and use a weapon against the instructor and students. How justifiable are their actions?

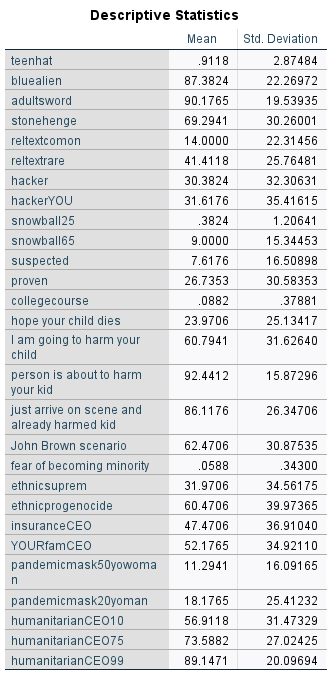

The remaining questions and results.

14-17. Someone tells you they hope that your child dies. You perceive this as a vague threat. Police say they cannot intervene and that you have no case.

(A) How justifiable is it to use violence to stop/ punish them?

(B) What if the person stated clearly “I am going to harm your child”?

(C) What if you saw them about to harm your child?

(D) What if you just arrived on the scene and they had already harmed your child?

18. A free person lives in a country that has had legalized slavery for over two centuries, which strongly goes against the person’s moral beliefs. They have pushed for it to be outlawed, but have no hope that it will be overturned. They decide to take up arms to free as many enslaved people as they can. They free no one, but kill a handful of pro-slavery people. How justifiable are the person’s actions?

19. A person feels that ethnic makeup of their city and country has been changing steadily over the past few decades, and that they are becoming a minority. They decide to enter a building that educates immigrants and start shooting people. How justifiable are the person’s actions?

20 & 21. A group of ethnic supremacists demonstrate in front of city hall. Their platform declares that other ethnic groups can live in the country, but they shouldn’t be allowed to vote, hold political office, or have a right to education. A larger group of counter-protestors start beating them severely. (A) How justifiable are the counter-protestors’ actions? (B) What if the ethnic supremacists’ platform is pro-genocide and declares that all people of a different ethnicity should be expelled from the country or be violently exterminated?

22 & 23. A person feels that health insurance companies have unfairly and regularly denied health care claims of sick people, leaving them to financial bankruptcy, deteriorating health, and sometimes death. They decide to take matters into their own hands and shoot a health insurance company CEO on the street. (A) How justifiable are the shooter’s actions? (B) What if it was YOUR favorite loved one who had been deathly ill and their claim that was denied? How justifiable would it be to shoot them?

24 & 25. In the middle of a deadly pandemic that has killed millions of people, a 50 year-old woman enters a small, crowded store and begins to cough loudly. Someone asks her to wear a mask over her mouth, but she refuses, saying that infringes on her freedom. Two other people start beating her severely. (A) How justifiable is the beating? (B) What if, instead of a 50 year-old woman, it was a 20 year-old man?

26-28. A new CEO of a large humanitarian group decides to end their organization. Normally, the org provided food and medicine for starving, sick children in poor countries. The CEO declares that they decided those children aren’t worth the money. Instead, they will spend the money on a school that trains elite athletes in the US. As a result, there is now a 10% chance that a million kids will die. A former aid worker threatens the life of the CEO.

(A) How justifiable is the aid worker’s threat?

(B) What if there was a 75% chance that a million kids would die?

(C) What if, instead of a school for athletes, the CEO said they would just keep all the money themselves, AND there was a 99% chance millions of kids would die?

Some observations: This was one of the highlights of the semester. Students were animated and said the survey made them think. I will certainly do this again in future semesters, and probably add/ subtract some of the scenarios (sadly, the world has an endless conveyor belt of new examples).

There was a range of opinion around the different scenarios, keeping in mind the caveats mentioned above (ex. lethal vs sub-lethal violence), and other limitations (this was a small sample of college students in Boston). I would say that the situations students found violence to be most justifiable revolved around the “moral foundation” of preventing harm. These included using violence to stop someone about to harm their child (mean 92.4) or to punish someone who had just harmed their child (86.2), to stopping an adult who was slashing people with a sword (90.2), to a blue alien about to wipe out half of humanity (87.4), to harming a CEO whose removal of humanitarian funds would create a 99% chance that a million children would die (89.1).

At the other end, shooting a child for throwing a snowball at a car driving 25 mph did not seem very justifiable (0.4) nor did using a weapon in a college course that taught ideas they disagree with (0.1), cracking a teenager’s skull for not removing their hat during the National Anthem (0.9), or because a person felt the ethnic makeup of their area had changed and that they were becoming a minority (0.1).

The other scenarios had wider disagreement, based on the boxplots and standard deviations. I asked students to consider which of Haidt’s 6 moral foundations might apply to some of the scenarios. For example, sending death threats to officials because of suspicion an election was rigged would apply to the notion of fairness, while not removing a hat during the National Anthem or threats to one’s preferred religious text or Stonehenge might apply to sanctity (the idea that some objects are sacred). And so on.

Ultimately, I left students with this passage from Aristotle to contemplate:

“Anybody can become angry; that is easy. But to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way—that is not within everybody’s power and is not easy.”

— Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (340 BCE)

Appendix

Dear Patrick,

As usual, thanks for a thought-provoking article. And as usual, I have some comments that don’t provide a ‘solution’ to a problem but widen our understanding of the problem within human society. (I am, after all, an anthropologist and motivated towards understanding Man, not changing Man.)

I would add a couple more scenarios to the list of practical situations you give.

The ‘socially sanctioned’, e.g. normal, violence committed with the tacit agreement of the ‘victim’. This is often linked to specific social norms which define a society and a member’s place in that society. Example: circumcision (male or female). This remains a norm within both Judaic and Islamic societies (I use ‘society’ rather than ‘religion’). My personal experience is witnessing the circumcision of 11-year old boys in Malay society. Malay uses the same term (masok Melayu) for both becoming Malay and becoming Muslim. Circumcision is delayed until around age 11 so that a boy is fully aware of it (and the temporary pain accompanying it). It is usually conducted in public, in a quasi-part atmosphere, with an invited audience including relatives and village neighbours and, if within that part of Malay identity based on matrilineal exogamous clan, with clan representatives. To refuse would be to refuse membership of the social group: it is a social obligation not a choice. But slicing off a foreskin (today with a surgically cleansed scalpel rather than a sharpened bamboo) is violence. It is agreed by the boy as a rite of passage — he stops being a child and becomes a man and is accepted as such by his society. Is such institutionalised violence justified? What if the rite of passage requires cutting off a finger? Or crushing one testicle with a rock? Or driving a rod through the penis and installing a penis pin?

My second example is taken from my elder brother’s experience when called up for national service. He did not want to go and pleaded pacifism: he would be not use in the army because he couldn’t kill and believed killing a human is wrong. He was examined. Not using physical violence but using similar questions to those you pose. Q. What would you do if somebody gratuitously hit you? Answer: turn the other cheek. Q. What would you do if you came home and found a man raping your mother or sister or wife? Answer: try to stop him anyway I could. Result: in he went.

Hi Robert,

Your comments always make me think and are warmly welcomed here.

You raise a good point about types of violence that are socially sanctioned, like rites of passage. I’ve seen definitions of violence and aggression that try to account for the motivations of the person on the receiving end of violence. For example, a person may “want” to endure the pain if there is a reward on the other side. Then again, I could imagine that they have little choice. Perhaps if given the option, they’d take the reward without the pain.

As for you brother, I think he gave a very reasonable answer, but the question was a trap. Joining a war is such a different scenario than defending a loved one in immediate need. I’m sure the interviewers knew it was a trap. And they probably didn’t care.