[Summary: This essay has three parts. First, truth is really important. Second, you are a damn fool. Well, not a fool. I’m trying to get your attention. But you are fallible, and so am I. We all are. This makes discovering truth very difficult. Third, our fallibilities can be exploited by others who do not particularly care for truth. Be humble, embrace your fallibilities, and try to overcome them as we strive towards accessing truth.]

“Being good, she observed, meant being good to others, including strangers. And that was pretty much enough to live by. But how can you know the right thing to do? Human reasoning, she said – referring now explicitly to Socrates and Plato – human reasoning is imperfect. Human bias keeps us from perfect vision of what is happening around us. But the quest for truth – the quest to understand the world around us – must ultimately be how you enact the good.”

– Alice Dreger’s mother (Galileo’s Middle Finger, p. 256)

“Veritas super omnia.”

.

Last year, I shared some thoughts on Isaiah Berlin’s 1994 essay, “A Message to the 21st Century.” Everyone should read it, in my opinion. I often come back to his words, as I see them as a synopsis of the human condition. Berlin emphasized that the values we hold most dear frequently clash with other ones (justice can clash with mercy, spontaneity with rational planning, liberty with equality, knowledge with happiness, etc.).

It’s straightforward, but also insightful. Berlin concluded that our only solution is to compromise at times in order to find a working, dynamic balance among our values. In his view, fanaticism and zealotry felt toward any single ideal should be curtailed. I think there is wisdom in this approach, and it may be an answer to many of the world’s problems – though maybe not the answer; there is no single answer that applies to all situations other than for a prudent give-and-take approach.

That general premise of balance and compromise can be found in other venues. The Bible says that “Man shall not live by bread alone.” Taken literally, this is true; it’s not merely a matter of what one shall, but what one can. No one can live on bread alone, or on rabbits, or coconuts. As omnivores, we cannot obtain all of our nutritional requirements from any single source. Of course, the Bible was referring to the notion that we should not only look to food for nourishment; we may also require spiritual nourishment.

We have various emotional needs as well. For example, infants who are deprived of physical contact do not grow as well, implying that nutrition is not enough – a sense of security (or feeling loved) is also vital (Field et al 1986). Similarly, in refugee camps, it’s not just calories that count. Laughter is also important, and it is said that “happiness matters like food.” The point is that we are complex, with a range of emotions, values, needs, and obligations at our disposal that are constantly in flux. We cannot be singularly committed to any of them. “Humans shall not live by anger-work-art-vitamin C alone.”

However, I could not help but notice that out of all the ideals he mentioned, Berlin referred to knowledge and the pursuit of truth as “the noblest of aims.” While he recognized that truth has its own trade-offs (his example was that knowing that one has a fatal disease is certainly not conducive to happiness), it stood apart as the pinnacle of human values. Even he had his favorites.

Philosophers have written extensively about truth, and I cannot do their work justice here. I’ll stick with the layman’s definition that the quest for truth is about making a sincere effort to seek out and describe the universe – and everything in it – as it truly is. Or, as Thomas Aquinas put it: “A judgment is said to be true when it conforms to the external reality.”

There are a few reasons this is important. Truth is egalitarian: it is accessible to everyone, provided they are clever enough and have access to correct information. Even if two individuals have different starting places, in seeking truth they should be able to arrive at the same destination. Obviously, this is theoretical; in practice, there are obstacles to truth and not everyone has access to the same information. But in a mechanical universe, reality has no motives to hide itself or reveal itself only to certain minds. It just is.

Additionally, from a social perspective, truth can tether people to reality across time and place. Imagine the opposite. The journalist Peter Pomerantsev, writing about fake news and fake reality television in Russia, said that “if nothing is true and all motives are corrupt and no one is to be trusted, doesn’t it mean that some dark hand must be behind everything?” Truth is also productive. Imagine trying to apply pseudoscience to reality, such as trying to prevent cholera based on miasma theory, exploring space based on a geocentric model of the universe, or promoting sugar as a diet aid. All of these examples will have, um, less than optimal consequences. For all these reasons and more, truth is essential. In fact, Gandhi went so far as to say that “Truth is God.”

“The word Satya (Truth) is derived from Sat which means ‘being.’ Nothing is or exists in reality except Truth. That is why Sat or Truth is perhaps the most important name of God. In fact it is more correct to say that Truth is God than to say that God is truth.” (MK Gandhi, 1932)

Like Berlin and Gandhi, and Alice Dreger and her mom, many others have placed truth on a pedestal, holding it above all other values:

- “The search for truth is the noblest of occupations, and its publication a duty.” (Anne Germaine de Staël, 1766-1817)

- “Truth conquers all things.” (Jan Hus, 1369-1415)

- Ibn Khaldun (1332 – 1406) Emphasized following “empirical facts.”

- “When you are studying any matter, or considering any philosophy, ask yourself only ‘What are the facts and what is the truth that the facts bear out?’ Never let yourself be diverted either by what you wish to believe, or by what you think would have beneficent social effects if it were believed. But look only, and solely, at what are the facts.” Bertrand Russell (1872-1970)

Of course, accessing truth is not a straightforward affair. We are all born ignorant about most things, and acquiring knowledge is a challenge. As a species, humans have benefited from our ability to discover, share, and accumulate knowledge over generations, locking in progress by holding onto things demonstrated to be true, while (ideally) shedding ideas shown to be false.

Cumulative learning. A mouse can only acquire knowledge it’s learned within a single lifetime. Each generation must start over. By contrast, humans can accumulate knowledge via language. (From: “The history of our world in 18 minutes,” by David Christian).

.Obstacles to Truth

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.” – Richard Feynman, Cargo Cult Science (1974)

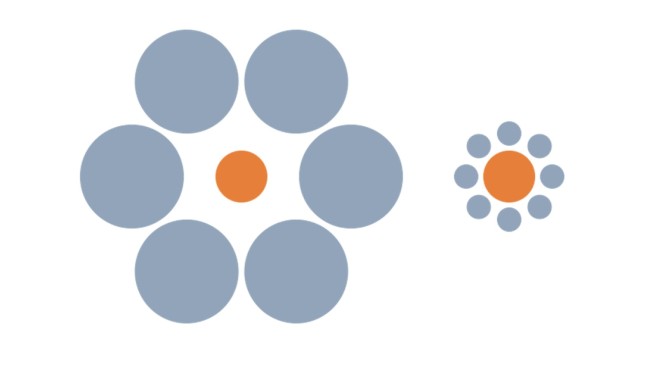

There are also substantial obstacles to discovering truth. As intelligent as we are, we still have a tendency to exhibit logical fallacies and cognitive biases (confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, overconfidence, etc.). We often have a hard time understanding statistics, and are also susceptible to visual illusions that are difficult to overcome (you can find some excellent examples here and here).

The Ebbinghaus illusion: the left orange circle appears smaller than the one on the right, but they are actually the same size. Source

Furthermore, it is simply beyond our ability to absorb all information simultaneously. Time and energy are finite, so we are forced to choose which questions to ask about the world, as well as which methods to use to answer them. And we are likelier to ask some questions than others, simply based on our backgrounds and circumstances.

Many people have addressed these issues. Psychologist Dan Ariely likes to say that we are “predictably irrational” in that much of our decision making is influenced by circumstances about which we are not always cognizant. Neuroscientist Beau Lotto said that “We don’t see the world as it is. It’s impossible to see the world as it is. We only ever see a world that’s useful to see.” In other words, our senses evolved to translate things like photons, molecules, and soundwaves into something adaptive from which our brains can make sense, but as Lotto noted, we don’t have direct access to the world. Our brains are always one step removed (at least), and we must always interpret information imperfectly. Similarly, biologist Ruth Hubbard (1988) reminded us that “knowledge about nature is an interplay between objectivity and subjectivity.”

Our subjectivity can never be overcome completely. We are not robots. Instead, we are susceptible to what has been called motivated reasoning, in that we have a higher standard of evidence for accepting new information that contradicts what we believe is true. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt summarized the concept of motivated reasoning this way: if we want to believe something, we ask ourselves “can I believe it?” If we don’t want to believe something, we ask: “must I believe it?” Much like a fishing basket, it’s as if we allow the flow of information easier access from particular directions, while making it harder to come from others.

Native American fishing trap from the Pacific Northwest. The analogy here is that the fish represent ideas, and our biases make it easier to accept ideas from certain directions (Source: Stewart 1977, p. 114).

People have tried to find ways to try to keep our subjectivity in check. Carl Sagan, who called science “a candle in the dark,” added that “science is more than a body of knowledge. It is a way of thinking, a way of skeptically interrogating the universe, with a fine understanding of human fallibility.” That fallibility never really goes away – it is built into us. In his book “Demon Haunted World,” Sagan listed a tool kit for skeptical thinking, to try – at least try – to keep our subjectivity in check. The kit is a good set of guidelines to figure out whether a claim is credible (added emphases are mine).

- Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

- Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

- Arguments from authority carry little weight – “authorities” have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts.

- Spin more than one hypothesis. If there’s something to be explained, think of all the different ways in which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the alternatives. What survives, the hypothesis that resists disproof in this Darwinian selection among “multiple working hypotheses,” has a much better chance of being the right answer than if you had simply run with the first idea that caught your fancy.”

- Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours. It’s only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will.

- Quantify. If whatever it is you’re explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations. Of course there are truths to be sought in the many qualitative issues we are obliged to confront, but finding them is more challenging.

- If there is a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work–not just most of them.

- Occam’s Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler.

- Always ask whether the hypothesis proposed can be, at least in principle, falsified. Propositions that are untestable, unfalsifiable are not worth much. Consider the grand idea that our Universe and everything in it is just an elementary particle – an electron, say – in a much bigger Cosmos. But if we can never acquire information from outside our Universe, is not the idea incapable of disproof?

An Internet of Brains

However, several people have pointed out that no individual human has the time or capacity to do the primary research themselves for every single detail about the world. Knowledge is a social phenomenon, and so much of what we know stems not just from personal observations and experiences but from what we learn from others. In Ruth Hubbard’s (1988) words, “One thing is clear: making facts is a social enterprise. Individuals cannot go off by themselves and dream up facts.” Much like the internet, our brains are interconnected through language and our shared experiences, from our elders, peers, and even people who lived long ago. The technology you’re using was invented by someone else (or multiple someone else’s over years). The book you’re reading was written by someone other than yourself. Even that language you’re speaking? Yep, someone else. We stand on the shoulders, and shoulder-to-shoulder, with giants and non-giants alike.

What that means is that we take in most of our information on some degree of faith, or trust, that our sources are credible. David Roberts at Vox put it this way: “for ordinary schmoes like us, developing beliefs about climate change centrally involves choosing who to trust. For the most part, it’s not first-order questions about evidence that make the difference, it’s second-order questions about who to believe.” Similarly, biological anthropologist Anne Buchanan wrote that:

“As scientists, our world view is supposed to be based on truth. We know that climate change is happening, that it’s automation not immigration that’s threatening jobs in the US, that fossil fuels are in many places now more costly than wind or solar. But by and large, we know these things not because we personally do research into them all — we can’t — but because we believe the scientists who do carry out the research and who tell us what they find. In that sense, our world views are faith-based. Scientists are human, and have vested interests and personal world views, and seek credit, and so on, but generally they are trustworthy about reporting facts and the nature of actual evidence, even if they advocate their preferred interpretation of the facts, and even if scientists, like anyone else, do their best to support their views and even their biases.”

Our interdependence upon others for information has costs and benefits. On the plus side, it is not up to every individual to reinvent the wheel; we can take what others have learned and run with it. But we can also be infected by bad information, some of it originating by error, some by malice.

This makes us susceptible to things like rumors. In a recent essay in Sapiens, anthropologist Hugh Gusterson discusses a number of rumors that people have accepted in various countries, and why people believe them. Examples include rumors in Brazil and South Africa that people were being killed for their organs and blood, respectively, and that health workers in Pakistan were sterilizing people via vaccinations. Gusterson added that rumors often reflect the underlying beliefs of what people consider plausible. He quoted another anthropologist, Karen Kroeger, who wrote that “rumors often circulate most intensively at times of uncertainty or unrest, (they) are more than just wrong or incomplete information; they are … a reflection of beliefs and views about how the world works in a particular place and time.”

On a personal note, when I was in graduate school, I had a discussion with an African American construction worker on campus. When it came up that I had interests in health within biological anthropology, he told me he was convinced that HIV was a conspiracy to kill people that the government didn’t approve of, including black people. Some of this he concluded from the perception that HIV seemed to come out of nowhere in the early 1980s, implying it was invented in a lab somewhere. But it was also based on what he knew about things like the Tuskegee syphilis study, when black men were misled for decades by government researchers who withheld treatment in order to understand how syphilis ran its course. The upshot of all this is that whether rumors are true or false, they can still teach us something, including who people trust and how they understand how the larger world works.

Our Faulty Sources: Infected by Post-Truths

“The most striking difference between ancient and modern sophists is that the ancients were satisfied with a passing victory of the argument at the expense of truth, whereas the moderns want a more lasting victory at the expense of reality.”

– Hannah Arrendt, “The Origins of Totalitarianism” (1973: 9)

There is another problem. Not everyone holds truth in as high regard as Isaiah Berlin, Gandhi, de Staël, Bertrand Russell, or Alice Dreger’s mother. Some hold it in disdain, or at least wish to halt its spread. Recently, some have claimed that deliberately false information has increased lately, leading them to conclude that we way be living in a “post-truth” era. A December 2015 poll found that the vast majority of Americans (88%) believe that intentionally fake news has created at least some confusion about what basic facts are.

It’s not just politics. Stanford University science historian Robert Proctor coined the word “agnotology,” the study of the deliberate propagation of ignorance. Examples include concerted efforts by governments, but also big businesses such as the tobacco industry who wish to cultivate ignorance and create the impression that no one knows exactly what the facts are. This is part of what Shawn Otto called “The War on Science.” Some have even claimed that “there’s no such thing, unfortunately, anymore of facts.” George Orwell warned against this in his 1943 essay “Looking back on the Spanish War” (please forgive the length of the quote, but it contains some timeless lessons).

“I am willing to believe that history is for the most part inaccurate and biased, but what is peculiar to our own age is the abandonment of the idea that history could be truthfully written. In the past people deliberately lied, or they unconsciously coloured what they wrote, or they struggled after the truth, well knowing that they must make many mistakes; but in each case they believed that ‘facts’ existed and were more or less discoverable. And in practice there was always a considerable body of fact which would have been agreed to by almost everyone. If you look up the history of the last war in, for instance, the Encyclopaedia Britannica, you will find that a respectable amount of the material is drawn from German sources. A British and a German historian would disagree deeply on many things, even on fundamentals, but there would still be that body of, as it were, neutral fact on which neither would seriously challenge the other. It is just this common basis of agreement, with its implication that human beings are all one species of animal, that totalitarianism destroys. Nazi theory indeed specifically denies that such a thing as ‘the truth’ exists. There is, for instance, no such thing as ‘Science’. There is only ‘German Science’, ‘Jewish Science’, etc. The implied objective of this line of thought is a nightmare world in which the Leader, or some ruling clique, controls not only the future but the past. If the Leader says of such and such an event, ‘It never happened’ — well, it never happened. If he says that two and two are five — well, two and two are five. This prospect frightens me much more than bombs — and after our experiences of the last few years that is not a frivolous statement.”

Such efforts to create confusion and keep people in the dark may be particularly effective in the Internet era, when dissembling can spread instantly across the globe and our motivated reasoning (see above) pushes us to look for facts that conform to our prior beliefs. There is evidence that fake news has been effective at confusing people. Americans of all political persuasions believe a number of claims that are without evidence.

Conclusion

So, what to do? Let’s return to Isaiah Berlin, who reminded us that values must inexorably clash. As you recall, Berlin’s most exalted value – truth – may clash with others, such as happiness. It is also clear that truth may clash with other more selfish desires, such as ambition and the wish to consolidate power. This is somewhat depressing, but there are some solutions.

First, a long look in the mirror is an essential place to start. The shortcomings we see in others reside within us as well. Having a healthy understanding of our own common shortcomings leads to possible solutions and workarounds. It’s why democracies try to build in checks and balances into the system (“If men were angels, no government would be necessary”). This is also why science has a system of peer review, to cross-check another’s work and to try to minimize our shortcomings. To return to David Roberts, he wrote that:

“We create institutions meant to counterbalance our worst demons, temptations, and limitations. […] Where confirmation bias, saliency bias, the bandwagon effect, and various other vulnerabilities to fallacy tend to reinforce myth and retard economic and technological progress, we create institutions to produce and rigorously vet knowledge, exposing it to dispassionate scrutiny and falsification. […] Luckily, society has created institutions specifically designed to produce valid knowledge. That’s all science is — just a network of human institutions with particular rules and practices.”

It also seems advisable to encourage curiosity. Yale behavioral economist Dan Kahan found that people who score higher on “scientific curiosity” may be less susceptible to “group think.” In other words, they, like Isaiah Berlin, value truth for its own sake.

There is a final reason to be optimistic about truth. Untruth has several advantages in that it need not conform to many rules. Nor does it have to be proven true – it can just linger, sowing doubt. Untruth can take various forms, and originate from unpredictable places. Because truth takes time and effort to get things right, untruth also benefits from its speed. As the old saying goes: “Falsehood flies, and the Truth comes limping after it.” However, while lies can sprint and spread rapidly, truth has endurance and the distinct advantage that it has a linear relationship with reality. Therefore, you can suppress truth, manipulate it, bury it, torture it. But you cannot kill it. Or, as Seneca the Younger stated almost two thousand years ago, “Veritas numquam perit.” (“Truth never expires”).

.

References

Arrendt H. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Link

Dreger A. 2015. Galileo’s Middle Finger: Heretics, Activists, and the Search for Justice in Science. Penguin Press. Link

Field TM, Schanberg SM, Scafidi F, Bauer CR, Vega-Lahr N, Garcia R, Nystrom J, Kuhn CM. Tactile/kinesthetic stimulation effects on preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 1986 May 1;77(5):654-8. Link

Hubbard R. 1988. Science, facts, and feminism. Hypatia. 1;3(1):5-17. Link

Pomerantsev P. 2014. Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia. Public Affairs. Link

Sagan C. 1995. Demon-haunted world: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Random House. Link

Stewart H. 2008. Indian Fishing: Early Methods on the Northwest Coast. D & M Publishers. Link