Summary: (1) Previous research shows that an immigration raid in Iowa in 2008 was associated with lower birth weight. (2) This was true of infants born to both foreign-born and US-born Latina women, suggesting this association centered around fear of being racially profiled, not merely immigration status. (3) Low birth weight is correlated with a range of health issues, including chronic diseases in middle age. (4) The scale of immigration raids today is much larger than 2008, affecting a wider segment of the population, increasing collateral damage among citizens. (5) One survey found that roughly 1 in 4 U.S. adults worry about deportation, with higher rates among immigrants and US born, second-generation citizens. This constitutes tens of millions of Americans, including an unspecified number of women of reproductive age. (6) In addition to human rights abuses, harsh deportation policies will likely lead to prenatal stress, impaired early development, and extensive long-term costs to public health.

.

.

.

“And you can see, you can hear, you could feel the fear, the intimidation. You could feel the terror.”

– Los Angeles resident Elizabeth Castillo, referring to local ICE raids (source)

.

In 2017, Nicole Novak and colleagues looked at the effects of a major government raid against suspected undocumented, primarily Hispanic, migrant workers in Postville Iowa (Novak et al 2017). In May of 2008, nine hundred ICE agents, along with a Black Hawk helicopter, raided a meat-processing plant in Postville, resulting in the arrests of nearly 400 workers. After a five-month prison sentence, 297 people were eventually deported. However, even those who were not deported (or even arrested) were affected.

Novak et al. looked beyond Postville for their sample, including 52,344 births across Iowa from 2007 to 2009. Infants who were born in the 37 weeks following the raid were classified as being prenatally “exposed” to the raid’s effects.

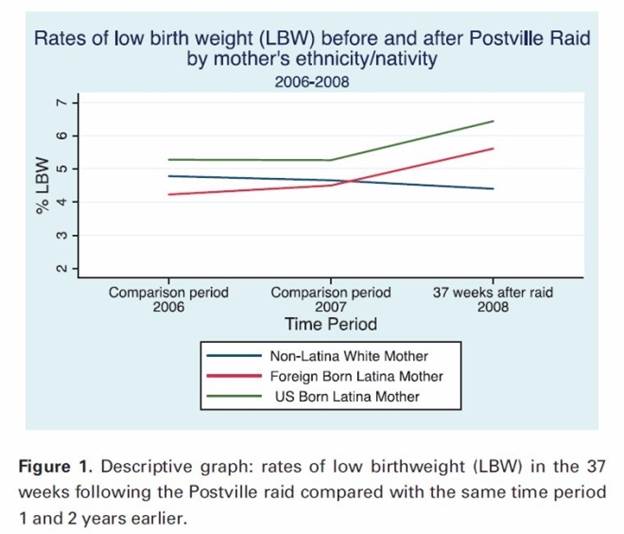

Results showed that for White and Latina mothers, rates of low birth weight (LBW) were steady before the raid. However, after the events at Postville, LBW rates increased by 24%, though only among Latina mothers. This was true for both foreign-born and U.S. born Latinas and their infants, demonstrating an effect that centered around ethnicity, not merely immigration status. This effect appeared to be greatest during the first trimester.

.

Because data were only available at the state level, Novak et al. were unable to determine if rates of LBW were even higher among Latina mothers who lived closer to Postville than those in more distant areas. However, the authors reasoned that Latina mothers throughout Iowa (and possibly outside the state as well) were likely aware of the raid, either by following the news or direct communications with friends and relatives. Given that rates increased among both U.S. born and foreign-born Latinas, it is certainly possible that Latina mothers felt vulnerable about raids targeting them for their ethnicity. If so, it is plausible that such stress could affect prenatal development and birth weight.

.

Prenatal Shocks

Several studies have found a link between prenatal stressors and reduced birth weight, including natural disasters; war; ethnic discrimination; and nearby explosions, deaths, or homicides. Even loud noise, such as living near an airport (Schell 1981) or working in a factory (Selander et al 2019), has been associated with lower birth weight. To that list, we can reasonably add fear of deportation and immigration raids.

The concern is not merely with LBW itself. Rather, LBW and intrauterine growth restriction are predictors for health problems later in life, per the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis. In sum, prenatal adversity and developmental deficits early in life are a risk factor for health deficits and chronic diseases later in life, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity, and osteoporosis, among others (Wadhwa et al 2009).

.

A Climate of Fear

Deportation has been a central focus of the Trump administration, putting the scale of the Immigration Customs Enforcement arrests and intimidation on a much different level than 2008. In fact, President Trump promised “the largest deportation operation in American history.” The nation’s attention has been captured by heavy-handed ICE tactics, a lack of transparency and due process, and the establishment of what have been credibly called concentration camps for migrants (here and here).

High-profile cases have added to the threatening climate, such as Tufts student Rümeysa Öztürk who was surrounded by masked, plainclothes agents in unmarked vehicles in Somerville, Massachusetts and then detained for six weeks. The same goes for Andry Hernandez Romero, a gay makeup artist from Venezuela who sought asylum in the US, but was instead sent to a notorious prison in El Salvador, where he was reportedly tortured, denied food, and sexually abused during his 125 days in captivity, all for the “crime” of having suspicious tattoos (many others have been sent to El Salvador as well). Being deported to third countries where people have zero ties or roots has happened in other cases, such as Jamaican and Cuban nationals convicted of crimes who were sent to Eswatini, with others sent to South Sudan. This pattern of deporting people to seemingly random third countries has alarmed human rights experts, who warn of the potential for torture, disappearance, and risks to life.

The intimidation factor appears deliberate. For example, in February “border czar” Tom Homan told a crowd “I’m coming to Boston. I’m bringing hell with me.” Similarly, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said she and federal agents (and other troops) were in Los Angeles “to liberate the city from the socialists and the burdensome leadership that this governor and that this mayor have placed on this country.” Los Angeles experienced what has been called the “summer of ICE”, along with the deployment of 700 Marines and thousands of National Guard troops in Los Angeles following anti-ICE protests. Threatening to rain hell on your own cities and suggesting that they needed to be liberated from elected officials aren’t things that are commonly uttered in a democracy. At least they didn’t use to be.

Even the cynically named “Alligator Alcatraz” is meant to intimidate, with Florida Governor Ron DeSantis telling reporters that undocumented people could choose to “self-deport” instead of being thrown in a place surrounded by intense heat and mosquitoes, “bloodthirsty” wildlife, maggoty food, and feces on the floor. Some Republicans have gleefully joked and fantasized that any escapees would be eaten. A report from Human Rights Watch revealed that some migrants at an ICE facility in Miami were shackled with their hands tied behind their backs and had to kneel so they could eat “like dogs.” All of this cruelty over what is most often, technically, a misdemeanor.

Nor have citizenship and legal status been guarantees of safety, further disseminating fear and widening the net. ICE and CBP have detained people who appeared in court for immigration hearings (thereby following the law), US veterans, US-born citizens with REAL ID, even children who are citizens (for weeks). One veteran was locked up for three days despite “no reason and no charges.” Another man died after falling off a building during a raid on a southern California marijuana farm, leading Governor Gavin Newsom to say “You got someone who dropped 30 feet because they were scared to death and lost their life… People are quite literally disappearing with no due process, no rights.” That notion of rights being steamrolled was echoed by Judge William K. Sessions of Vermont, who said Rümeysa Öztürk’s arrest and detention “raised a substantial claim of a constitutional violation” and was likely retaliation for something as trivial as an op-ed she had written about her university’s response to the situation in Gaza.

I cannot describe every high-profile case, nor adequately cover all the injustices that have been done. The point is that these policies have created a widespread sense of dread, anger, and dissatisfaction. A CBS/ YouGov poll this month (July 2025) found that 58% of Americans were opposed to the way the Trump administration has used detention facilities for deportation, including 93% of Democrats and 66% of Independents (versus just 15% of Republicans, who are more apt to favor mass deportation).

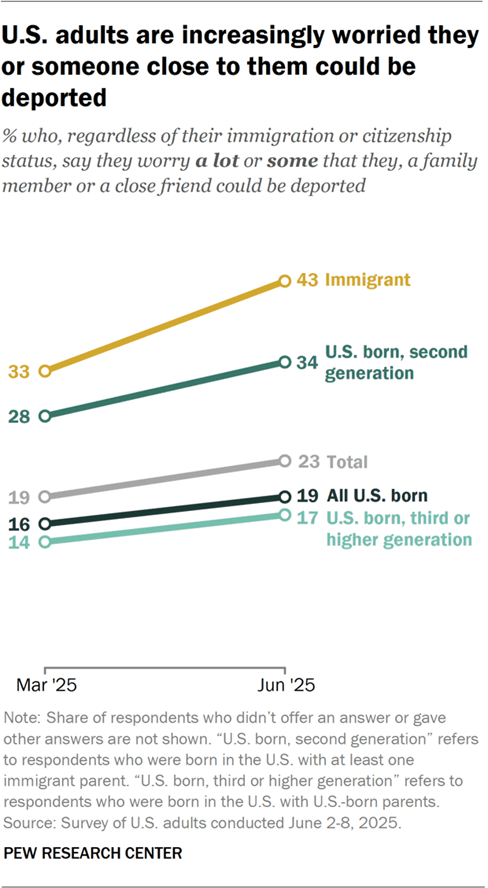

Another June 2025 poll from the Pew Research Center found that 23% of US adults worry that they or a loved one could be deported (it would be revealing if people were asked about not just deportation but also about fear of arbitrary detention). Rates of worry were higher among immigrants (43%) and US born, second-generation citizens (34%). Hispanic adults were most worried about deportation (47%), followed by Asian (29%) and Black (26%) adults, with white adults having the lowest rates of worry (15%). Altogether, this means tens of millions of Americans, including an unspecified number of women of reproductive age, are worried of deportation to some degree. This indicates many pregnant women will experience heightened levels of stress, impacting prenatal development.

.

.

Those worries will likely get more intense. The Trump/ Republican budget will substantially increase ICE’s annual budget from $8.7 billion to $27.7 billion, which many have pointed out is larger than the militaries of most countries. However, the typical mission of a military is directed at extra-national targets and threats, not the domestic population. This is also something not common for a democracy. Again, at least it didn’t use to be.

.

The Damage Done

When you impose a climate of fear on a population, it would be irrational to expect no collateral damage. Fear is obviously a complex and subjective experience (Grogans et al 2023), but most people would agree that it is an unpleasant one. Disrupting a single life via the imposition of fear is no small thing; disrupting tens of millions of lives will inevitably incur costs. In Los Angeles for example, so many people are afraid to leave their homes for fear of being arrested and deported that the Catholic archdiocese plans to deliver food and medicines to some of its parishioners.

It seems obvious that we would want to protect mothers and their fetuses from outside stressors to give them the best chance at a healthy pregnancy and a good early start in life. While some prenatal shocks like natural disasters and earthquakes are beyond our ability to control, other shocks are anthropogenic, and the result of choices, policies, and (ultimately) values. They are therefore within our power to curtail, with potential payoffs in terms of development, overall well-being, and reduced health care costs. That is, if powerful people even care about those things.

.

References

Grogans SE, Bliss-Moreau E, Buss KA, Clark LA, Fox AS, Keltner D, Cowen AS, Kim JJ, Kragel PA, MacLeod C, Mobbs D. The nature and neurobiology of fear and anxiety: State of the science and opportunities for accelerating discovery. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2023 Aug 1;151:105237. Link

Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. 2017. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. International Journal of Epidemiology. 46(3): 839-49. Link

Schell LM. 1981. Environmental noise and human prenatal growth. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 56(1):63-70. Link

Selander J, Rylander L, Albin M, Rosenhall U, Lewné M, Gustavsson P. 2019. Full-time exposure to occupational noise during pregnancy was associated with reduced birth weight in a nationwide cohort study of Swedish women. Science of the Total Environment. 15;651:1137-43. Link

Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S, Swanson JM. 2009. Developmental origins of health and disease: brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 27 (5): 358-368. Link

[like] Amy Todd reacted to your message: