Last week, Elon Musk wrote that “USAID is/was a radical-left political psy op,” as a partial explanation for his desire to close the organization. I am not an expert on the entire history of USAID (United States Agency for International Development), but I do know a little something about one particular episode in its past that contradicts Musk’s claim.

Long ago, I wrote my dissertation about some of the long-term health impacts of the civil wars in Laos from the 1950s-70s. That required interviewing and assessing Laotian refugees. It also meant delving into different subjects, including the biology of what was then called the “fetal origins hypothesis,” today commonly known as the DOHaD idea. It also meant plunging into the history of the wars and how the civilian population fared. I found the history fascinating, involving a revolving door of royalists, communists, and “neutralists,” featuring Laotians themselves, but against a backdrop of French colonialism, Japanese occupation, and later intervention by Vietnam, Thailand, and of course the United States.

After the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in northern Vietnam, one of the stipulations of the 1954 Geneva Accords was that Laos would remain a neutral country, free of foreign troops. Eventually the US took a circuitous route around this in its fight against Laotian and Vietnamese communists, by funding both the Royal Lao Army and a clandestine network of special guerilla units (SGUs) in the countryside, primarily Hmong and other hilltribes (so-called Lao Sueng, or Lao of the mountaintops). This became known as “the Secret War” because much of this was unknown to the American public, and most of Congress.

Here is where USAID comes in.

Laos was a poor country, with an estimated 90% of the population being rural agriculturalists. The creation of SGUs disrupted traditional farming life by creating a shortage of male labor since they were off fighting or were killed (casualty rates were high). SGUs were also relocated to important military outposts. To maintain the morale of this anti-communist army, soldiers were encouraged to bring their families with them to these outposts, including Long Chieng (Quincy, 2000: 239). Long Chieng was situated about 240 km north of the capital, Vientiane, and was at one point a center for 6,000 refugees, run by USAID and a 50 year-old farmer from Indiana named Edgar “Pop” Buell (Schanche, 1970: 134). As a 40-something year old widower, Buell had volunteered for the International Voluntary Services to become an agricultural adviser, and was stationed in Laos. Eventually, he would come to coordinate with the newly created USAID in the early 1960s.

When the well-known Hmong officer Vang Pao, who would later be promoted to General, saw the strategic advantages of Long Chieng with its long runway, remote location, and the protection of karst mountains, he made it his military headquarters. Buell and the refugees moved 17 km up the road to Sam Thong “in order to maintain at least the appearance of separation between civilian and military affairs” (Schanche, 1970: 134). In reality, civilian and military operations were very much intertwined. Reportedly, Vang Pao told Buell that “without your airlift, all of my people would have starved. I can organize an army and fight, but I must have you to help the civilians. Without the support of the people my soldiers cannot live” (Schanche, 1970: 85).

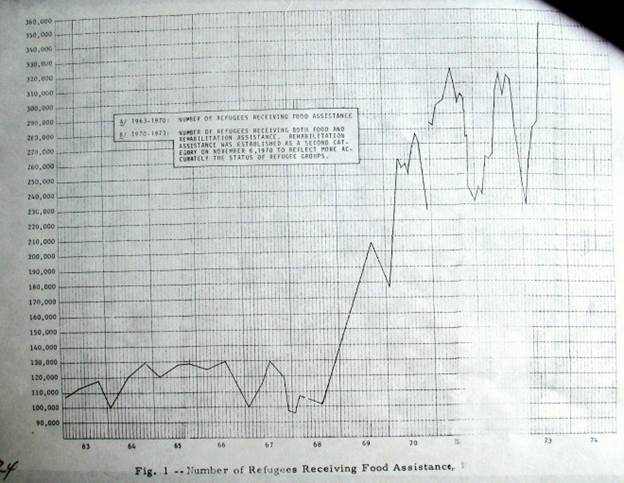

One effect of all this was that it kept Hmong and other civilians dependent upon military pay and other external, humanitarian support, largely provided by USAID. Families of soldiers and refugees were supplied with USAID food, clothing, and tools by the in direct collaboration with U.S.-sponsored paramilitary efforts (USAID, 1976: 171). According to internal documents, the number of refugees that received USAID assistance remained between 100,000 and 130,000 from 1963 to 1968, jumping to over 200,000 in mid-1969, and peaking at 353,297 in late June 1973 (USAID, 1973: 22-4).

Regardless of how one feels about the US intervention in Laos or USAID, it is a fact that they played an integral role in counteracting communism in Laos. This was no minor effort either, supporting hundreds of thousands of people over a decade in a battle that would ultimately be lost.

For Musk to claim that USAID has been “a radical-left political psy op,” he would have to ignore much of its history. In fact, the federal Office of the Historian wrote that the reason USAID was created at all was to help serve as “a bulwark against a perceived communist threat” through humanitarian diplomacy, which would directly contradict Musk’s claim. But I get the feeling that he isn’t interested in historical accuracy anyway. He is more interested in using his global megaphone to craft a narrative that suits his motives. Meanwhile, it is probable that many people will suffer as a result.

References

Quincy K (2000) Harvesting Pa Chay’s Wheat: The Hmong and America’s Secret War in Laos. Spokane, WA: Eastern Washington University Press.

Schanche DA (1970) Mister Pop. New York: McKay.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (1973) Facts on Foreign Aid to Laos, July, Internal ref. #: PN-ABI-555.

United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (1976) Termination Report USAID Laos, January 9, Internal ref. # PN-AAX-021.

Thanks, Patrick, for revising a little the role of USAID (at least in Laos 1960s-70s). During the early 1970s (when I was there doing fieldwork), USAID was huge. Not everybody in it was nasty, and like any massive organisation there were some positives, although these in no way balanced the negatives. The large Vientiane suburb at KM6 is still where it was when built to house USAID and others, mostly US, within Laos. Even the name remains the same: KM6. It was part of history’s paradox that the nicely laid out little bit of America in Laos provided an instant home, with debating chambers, housing, and even security, for the Party, those involved in running the country, and retirement homes for those who had fought for the winning side. In terms of infrastructure, little has changed there other than USAID and associates leaving. It still sometimes surprises me to drive around what might be a suburb of Minneapolis and see the Lao families in KM6 — although almost all of the ‘old soldiers’ are now dead (although General Siphandone celebrates his 101st birthday next week!). I remember around May 1975, the PX closing as the last of USAID left. There was no conflict within Vientiane and, thankfully, no scorched earth policy. Thus, as PL officials came in from VX mid-June on, they took over US-made aircon housing. From the caves to a US suburb! Other remnants of USAID remembered were the Pepsi-Cola factory on the Mekong that never actually produced any Pepsi but served (it is said) as a giant heroin refinery (it now makes Beer Lao), and a bowling alley on Thadeua KM4. And of course the Hmong town created by USAID at KM52 (which still retains the name KM52) — at the time the 2nd largest concentration of Hmong outside Long Chen — where some 7,000 Hmong, obliged by the secret army to leave X Khouang, were relocated. All in all, the history of USAID in Laos was one of picking up the pieces after the CIA army and the Thailand-based bombing runs. If it has changed from the quasi-civilian side of right-wing adventurism to an international left-wing conspiracy, that’s certainly an improvement. However, that seems unlikely. All best wishes, Robert

Thank you, as always, Robert. Your first-hand knowledge on these things is invaluable. Have you written all of this down somewhere? Also, could you provide an example or two of some of the nasty and the negatives from USAID? I mostly read their own reports (on microfilm!) and interviewed one former employee who was there at the time.

Hi Patrick, I have avoided a ‘memoir’ (at 79, I’m far too young!) but have sought to debunk some of the most outrageous myths of history in ‘Laos: Making History’. This book (c. 400 pages) is currently printing a special Laos edition to begin commemoration of 50 years of Lao PDR. I attach front and back covers. This edition is with approval (even praise!) of the Ministry of Culture. It will only be available in Laos (from next Saturday) until an international edition appears, maybe mid-year (depends on international publisher). The ‘Making’ in the title is the key word. Just about all known history was ‘made’ in the sense of ‘made up’ — even going back to the formation of Lan Xang (I was surprised the ministry — which took 6 weeks to examine the text actually approved that part!). I have also had access to some unusual sources (including the UK Foreign Office — since I was once Brit Rep here) and conclude that the hero Chao Anou would almost certainly have beaten the Siamese army outside Bangkok had Siam not been provided with modern weaponry by the UK (and the US) following the defeat of Napoleon — such UK weapons being in exchange for the ‘Malay States’ occupied by Siam. I cover the forced relocation of Hmong and Khmu historically — USAID’s involvement was but a continuation of a historical pattern. I don’t target USAID specifically — there would be too much were I to go into such projects as cattle farms and Ginseng plantations — as few projects actually materialised much beyond budgets. I would stress that not all involved were deliberately hostile and that there was a difference between USAID & CIA. However, even the ‘good’ projects like caring for internal refugees existed only because the military wing of US ‘aid’ had displaced farmers. I also correct the assumption that Hmong fought only for the CIA/monarchy. I knew and worked closely with Faydang Lobliayao and he chatted quite freely about the split between Hmong. Faydang was Hmong Njua (Green) whereas Vang Pao was Hmong Deu (White) and there was a split of sorts along those lines. It is also important that while more Hmong fought for Vang Pao (or rather for the pay — much more than the Royal Lao Army), far more Khmu fought for the Pathet Lao. — by the way Pany Lobiayao is now the vice-president — creating the possibility that within a few years Laos will see its first female (and Hmong) president. Kayson and Faydang both had houses allocated to them in the ex-USAID compound but chose to live outside of the ‘ghosts’. Faydang in fact lived most of his time at That Dam in a French house right next to the US mission. I was always welcome in his house — as were any Hmong passing through. Faydang’s life particularly has been twisted by those Paoists in the US. The simple fact is that Faydang helped Syong Leu (the ‘passivist’ Hmong imprisoned and assassinated by Vang Pao) and he was very much open to shades of political opinion other than extreme right — while recognised as one of the 4 national heroes, he never joined the Party. I don’t expect my History to make me any friends in the US, although some of those who threatened my life in Minneapolis have written to me in a tone of let bygones be bygones, so I remain somewhat optimistic that those Hmong in the US might eventually get round to revising their own history. My book is not only about Hmong. My time with ‘Thai-Khao’ in Vietnam has also proved very useful in reformulating history. It is clear to me that the devilish ‘Black Flags’ were indeed from Vietnam (although it didn’t exist at the time) — but they had red flags, spoke Thai-Khao (much like Luang Prabang Lao) and fought against Siam’s occupation of LPG. Anyway, it’s a long story. If I can’t get a book to you, I’ll send a pdf text. Carry on the good work, Patrick. — by the way, do you know Gerry Fry (U Minnesota) — about to finally retire from faculty (at my age!) — a good friend. Cheers, Robert

When that book is available, I’ll be sure to get a copy, Robert. Yes, 79 is young these days, at least outside of the US since stress levels are pervasive here. I hadn’t heard the term “Paoists,” but it made me chuckle. In French Guiana, the Yves Bertrais Hmong there referred to their brethren in the US as “Vang Pao Hmong.” I don’t know Gerry Fry, unfortunately.