Darieliz Michelle Lopez, her 20-month-old son and three-year-old daughter sit on a sofa where her apartment stood in San Isidro on Sept. 28. (Andres Kudacki for TIME)

In 2013, Orlando Sotomayor, a professor of economics at the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez, looked into whether two hurricanes in 1928 and 1932 impacted the long-term health of the people of the island. He specifically explored whether people exposed to the hurricanes prenatally had higher rates of various chronic diseases and lower education levels decades later.

He framed this within what used to be referred to as the fetal origins of disease hypothesis, but is now usually called the DOHaD (developmental origins of health and disease), acknowledging the importance of development beyond the fetal period. In a nutshell, the DOHaD is based on decades of evidence that various biological insults (malnutrition, maternal psychological stress, pollution) in the prenatal and early postnatal stages of life may predispose individuals to chronic diseases later in life. This has been linked to type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hypertension (Barker 1994), schizophrenia (Wahlbeck et al 2001), osteoporosis (Cooper et al 2009), and possibly cancer (Walker and Ho, 2012).

In one of the best-known examples, women who were pregnant during the Dutch “hunger winter” in World War 2 had offspring who had a higher risk of various conditions by the time they reached middle age, including a doubled rate of coronary heart disease, obesity, and diabetes in adulthood (Rooseboom et al 2011). They also had an increased chance of having schizophrenia and depression, and did worse on cognitive tasks. While famine conditions are not necessary to have such impacts (poverty and deprivation operate in a dose-like fashion), the well-defined period of the “hunger winter” provided a way to compare exposed and unexposed persons.

The 1928 and 1932 Hurricanes

Professor Sotomayor viewed the decades-old hurricanes in Puerto Rico as akin to something like the Nazi-imposed famine in the Netherlands. There are differences, obviously. Disasters resulting from intentional, anthropogenic (human-generated) disasters like war usually end up leading to protracted humanitarian crises (Schultz et al 2014). While natural disasters are often devastating, they are usually short-lived and can be ameliorated by humanitarian aid, whereas unsafe conditions during war often makes such assistance logistically difficult. Of course, aid following natural disasters depends on the scale of destruction, a country’s pre-disaster wealth and access to resources, and the political willingness of neighboring countries to assist.

Hurricane San Felipe (1928) and hurricane San Ciprian (1932) both had devastating effects on the agrarian economy of Puerto Rico, with damages estimated to be about one-third and 20% of national income, respectively (Sotomayor, 2013: 282-3). Coffee, citrus, and sugar cane crops were particularly affected. Using data from the CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys, Sotomayor looked at people born between 1920 and 1940, and defined those individuals born in the years immediately following the hurricanes (1929 and 1933) as having been exposed to difficult early life conditions. Unfortunately, month of birth was not available in the dataset, so year of birth had to suffice.

Plantain trees flattened by Hurricane Maria in Yabucoa, P.R. In a matter of hours, the storm destroyed about 80 percent of the crop value in Puerto Rico, the territory’s agriculture secretary said. Credit Victor J. Blue for The New York Times

In all, the sample comprised 11,990 individuals, with 1,197 defined as being exposed to the effects of the hurricanes in early life. Overall, he found that exposed individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes, as well as be more likely to have no formal schooling. This latter outcome variable was interpreted as possibly being a “cognition shock,” suggesting that exposed individuals may have had some decline in mental faculties resulting from poor early neurological development.

Incidence (and 95% confidence intervals) of chronic diseases and lack of schooling in Puerto Rico by year of birth. People born in 1929 and 1933 were viewed as being exposed to the effects of a hurricane in early life (Sotomayor 2013).

After Hurricane Maria

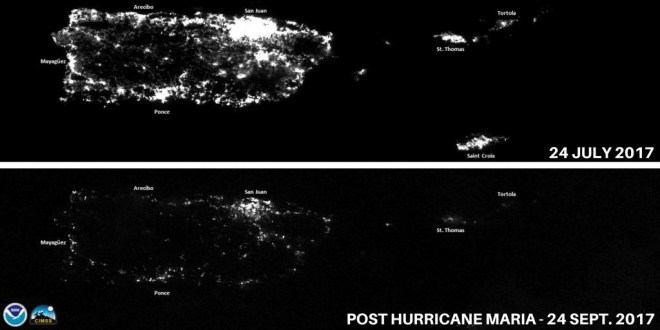

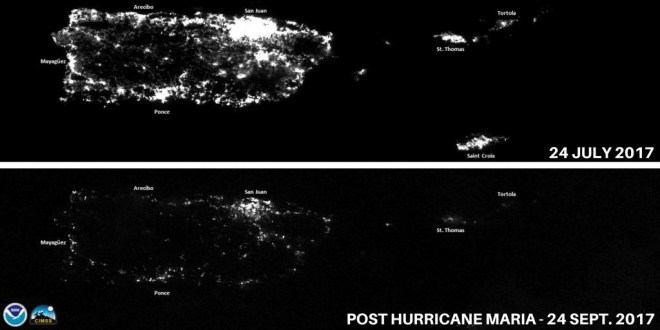

We can speculate whether something similar might result from hurricane Maria, which made landfall on Puerto Rico on September 20 of this year. As a Category 5 hurricane, it was among the most powerful ever recorded and its devastating effects likely won’t be resolved anytime soon. It has been estimated that more than 1,000 people died as a result of Maria, while a substantial proportion of the population still remains without electricity, months later.

Similarly to Hurricanes San Felipe and San Ciprian, Maria destroyed up to 80% of Puerto Rico’s agriculture, and rates of food insecurity have increased (rates were already high before the hurricane). Reports indicated that following the hurricane, many people on the island had to skip meals and waited in lines for hours waiting for emergency food supplies, as relief supplies were below standards that were available in other recent hurricanes that hit Texas and Florida (even though all are American citizens). According to CBS News, more than 215,000 people left Puerto Rico for Florida between October 3 and December 5, and it’s been projected that perhaps more than 470,000 people will leave in the next two years (and up to 750,000 people over the next four). Proportionally, this is a staggering loss of population on an island that had 3.4 million people in 2016.

A combination of NOAA satellite images taken at night shows Puerto Rico in July, top, and on Sept. 24, 2017, after Hurricane Maria knocked out the island’s power grid. NASA/NOAA/Handout/Reuters

All of this suggests that there is the potential that Maria could have long-term effects on health, growth, and development similar to San Felipe and San Ciprian. Early life is a particularly vulnerable period, and there are an estimated 175,000 children under the age of to 4 years old on the island. Growth rates are fastest in this stage, and the potential for long-term effects on health should factored into Maria’s costs beyond the effects on mortality, damaged infrastructure, destroyed crops, economic losses, and displaced population. It also hints at the urgent need to summon the political will to respond rapidly and sufficiently to minimize the effects of natural disasters like this. Otherwise, the costs will have to be paid later in terms of loss of health, premature death, and possibly diminished cognitive capacity (and all of its concomitant costs to education and economic potential). As Professor Sotomayor wrote (2013: 291):

“Evidence therefore suggests that in absence of preventive measure, effects of events like Bay of Bengal cyclones, Caribbean Sea storms like hurricane Mitch, or the great Haitian earthquake may not be over for a long time.”

References

Barker DJP. Mothers, Babies, and Disease in Later Life. BMJ Publishing; 1994.

Caruso GD. The legacy of natural disasters: The intergenerational impact of 100 years of disasters in Latin America. Journal of Development Economics. 2017 Jul 31;127:209-33. Link

Cooper C, Harvey N, Cole Z, Hanson M, Dennison E. 2009. Developmental origins of osteoporosis: the role of maternal nutrition. Early Nutrition Programming and Health Outcomes in Later Life. 2009:31-9. Link

Shultz JM, Ceballos ÁM, Espinel Z, Oliveros SR, Fonseca MF, Florez LJ. 2014. Internal displacement in Colombia: fifteen distinguishing features. Disaster Health. 2(1):13-24. Link

Sotomayor O. Fetal and infant origins of diabetes and ill health: Evidence from Puerto Rico’s 1928 and 1932 hurricanes. Economics & Human Biology. 2013 Jul 31;11(3):281-93. Link

Wahlbeck K, Forsen T, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG. 2001. Association of schizophrenia with low maternal body mass index, small size at birth, and thinness during childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 48-52. Link

Walker CL, Ho SM. Developmental reprogramming of cancer susceptibility. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012 Jul 1;12(7):479-86. Link