“I think the human race needs to think more about killing, about conflict. Is that what we want in this 21st Century?”

– Robert McNamara, The Fog of War (2003)

.

“How careful should we be, that we do not mistake the impressions of gloom and melancholy, for the dictates of reason and truth. How careful, lest borne away by a torrent of passion, we make shipwreck of conscience.”

– John Adams (November 29, 1770)

.

“We’ll see you at your house. We’ll murder you,” the young woman threatened the Bakersfield City Council. “The entire nation is coming for you. And we will stop, at no end, until you are in the ground. You’re a traitor to this nation,” said the man’s voicemail left for the Arizona Secretary of State. “I hope they kill your children,” shouted the murdered child’s relative at their alleged killer in a Houston courtroom. Gay people should be “lined up against the wall and shot in the back of the head,” preached the Texan pastor. “Yes I do, I support genocide. I support killing all you guys, how about that?” the campus safety officer told a group of protesters at CUNY.

..

I’ve been thinking for a while about how people determine when violence is acceptable. For that reason certain news stories jump out to me, particularly those close to home in the increasingly angry United States. I don’t have all the answers, but I think that within many (or most?) of us is a something akin to a black box of violence, when anger reaches a point that people feel compelled to threaten, harm, or even kill. As Lincoln wrote: “Blood grows hot, and blood is spilled.” Yet how this all operates under the hood is somewhat nebulous, and I think people have their own idiosyncratic formula for what makes their blood “hot” and what they decide to do about it. The hope is that bringing these subconscious inclinations closer to the surface might give us a better understanding, and possibly control, over them.

The psychologist Tage Rai and colleagues distinguished between two main motives for violence. The first was instrumental violence, where someone harms another as a byproduct of some other objective, such as armed robbery or the “collateral damage” of civilians harmed in war. Dehumanization can creep in here, facilitating instrumental violence by denying others’ human qualities or comparing them to other species or diseases.

But to me Rai’s second major motive, moral violence, is more compelling. In other words, we may feel violent toward someone not necessarily because we think they are sub-human, but because we believe they were bad humans, that they failed to live up to our moral standards in some way and deserve to be punished for it. Rai argued that most violence is morally motivated.

To Rai, this isn’t the way most of us think of violence. Rather we tend to believe that people become violent because of an impulsive breakdown in morality; instead he suggested, the opposite can also be true: that we may have an “excess” of morality, where people can feel compelled to punish others for their suspected moral failings.

This doesn’t mean of course that such violence is objectively morally justified. Rather, it simply suggests that the people wielding violence merely believe that it is, according to their values. And because values and morals are pliable among individuals and across cultures, there are so many ways to perceive others as failed moral agents. As Workman et al (2020) wrote: “People who bomb family planning clinics and those who violently oppose war (e.g., the Weathermen’s protests of the Vietnam War) may have different sociopolitical ideologies, but both are motivated by deep moral convictions.”

What behaviors violate your moral red lines will likely differ from someone else’s, based on a number of factors: how you were raised, your individual personality, recent stressful events in your life (a powerful predictor), the quality of the information you’ve received and how it was framed, perhaps what media sources you follow, the level of the perceived offense, and who the offending party is and whether they are an “us” or a “them.” As imperfect people, we use imperfect minds to make imperfect decisions using imperfect information. Yet those messy decisions—which we can perceive as having morally clear answers—can have messy, permanent effects.

Neurobiology and Moral Foundations

Let’s return to the examples of people threatening violence at the top of this essay. As reprehensible as they are, they all touch raw moral nerves. The Bakersfield woman was ostensibly angry because she perceived the city council members as being “horrible people” indifferent to others’ suffering, including those in Gaza. She also seemed upset at new security measures to the council chambers, which she viewed as oppressive and “criminalizing” of local constituents. The Arizona Secretary of State, like many officials across the country, were painted by the political right as having overseen fraudulent elections; this speaks to (perceived) unfairness, particularly when seen as perpetrated against their ingroup. The relative in Houston was obviously distraught by the injustice and fatal harm caused to the murdered child. The Texan pastor was likely motivated by a sense of disgust toward beliefs about sexual impurity. The CUNY officer’s thinking is less clear. Perhaps it’s a clear-cut situation and he actually does support genocide. Or perhaps he was upset by the idea that a graduation ceremony was being disrupted and a perceived lack of deference to authority and social order. All of these speak to what psychologist Jonathan Haidt calls a basic set of moral foundations, contingent upon which values we prioritize.

According to Workman et al. (2020) in their article “The Dark Side of Morality,” the neurobiology underpinning social cooperation and competition in humans overlaps largely with that found in other primates via similar fronto-temporo-mesolimbic circuitry, indicating that this may be evolutionarily ancient and largely preserved in us. Yet they also wrote that “violence motivated by moral convictions, which is seen as both proper and necessary for regulating social relationships, is specific to humans.” Specifically, fMRI experiments revealed that “Believing violence to be appropriate was associated with parametric increases in vmPFC (ventromedial prefrontal cortex), while stronger moral conviction was associated with parametric increases in VS (ventral striatum) and, overall, correlated negatively with activation in amygdala.” In support of this, they cited another study in Pakistan that pointed to the activation of the vmPFC being correlated with a willingness to fight and die in Kashmir.

The pathways and mechanisms may or may not be of interest to most people, but I think it might help us to pause and consider what is happening within us when ideological violence begins to feel morally justified. Furthermore, Workman et al noted that we seem to have “a natural aversion to interpersonal harm,” which can be overridden by other subjective moral convictions. This isn’t to sound pollyannish, but I think it helps to remember that our “default” setting is largely nonviolent, rather than vice versa. Despite concerns about the increased acceptance of ideological violence, most Americans still agree that it is reprehensible.

Trends in Threats and Violence

It’s true that ideological violence, with various ideological underpinnings, has increased in the US. The FBI reported that hate crimes reached an all-time high in 2022 with 11,634 cases, more than double the 5,462 cases reported in 2014. (Preliminary data from major cities indicated that these numbers were likely even higher in 2023). Hate crimes based on race/ethnicity (particularly anti-Black) comprised the largest share, followed by those directed against religious groups (primarily anti-Jewish), and against LGBTQ groups, with a notable uptick (40%) in hate crimes against anti-transgender people. This is likely correlated with the rise in anti-trans rhetoric; as is often true with ideological violence, the fomenting of anger through speech often precedes action.

In recent years, we have seen high-profile cases of political violence as well, including the shooting of Republican members of Congress while they practiced for a baseball game, an attempted stabbing of Republican Lee Zeldin on stage, a home invasion and vicious hammer assault of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s husband, threats against Supreme Court justices, threats against Colorado judges and the Maine Secretary of State who ruled against Trump appearing on the ballot. And then of course, there was Jan 6th. It’s honestly hard to keep up, and I must omit some examples for the sake of space (and my sanity; this is all pretty depressing and disappointing stuff).

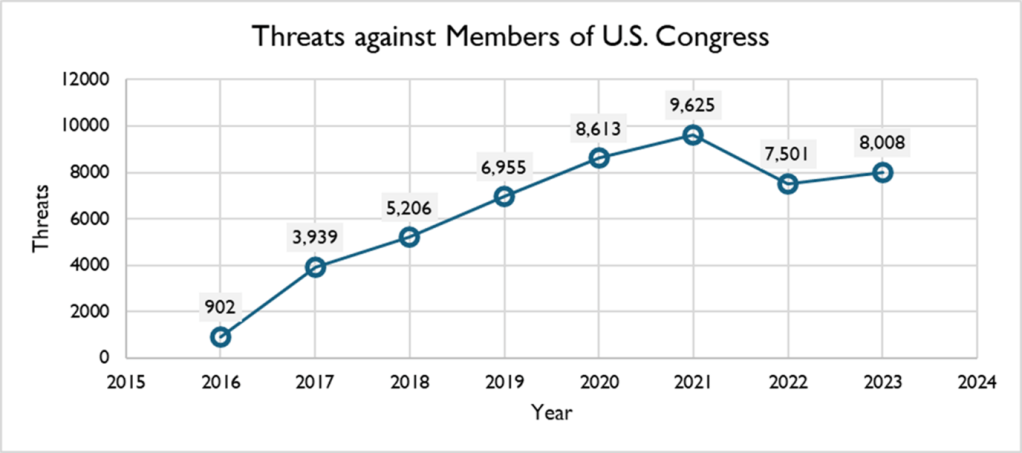

Statistics help us get a sense of the scale of the problem. In 2021, U.S. Capitol Police Chief Tom Manger said that “We have never had the level of threats against members of Congress that we’re seeing today.” By the end of that year, there were 9,625 threats, versus just 902 in 2016. They decreased a bit the following year, but saw a slight uptick from 2022-23. Similarly, total domestic terrorism cases investigated by the FBI have increased. From 2013-16, they declined from 1,981 to 1,535 cases, but then rose dramatically to 4,092 by 2019 and to 9,049 by 2021 (GAO 2023).

Data from US Capitol Police.

.

On top of this, we have seen increased threats made at the local level, against city council members, school boards, hospitals, multiple universities, health workers, and election workers, with the perpetrators likely believing their actions are justified.

To get an overall sense of trends, The Prosecution Project has compiled an open-source database of 4,136 felony criminal cases involving illegal political violence in the United States since 1990. Of these, 50.9% were attributed to people with right-wing motives, 22.3% to Jihadist motives, 13.0% other, 11.2% left-wing, and 2.6% nationalist/separatist. Since 2015, the number attributed to right-wing suspects has increased to 59%. Changes in attitudes toward justified violence underlie these numbers.

Political violence cases by ideology in the U.S., 1990-mid 2024. Source: the Prosecution Project.

.

.

In an April 2024 Marist poll, 79% of Americans disagreed with the statement that “Americans may have to resort to violence in order to get the country back on track” (87% of Democrats, 82% of Independents, and 70% of Republicans). Ideally, those numbers should be much higher, though they still represent a significant majority. A separate 2022 poll conducted by researchers at the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program (VPRP) found a comparable pattern, with 20.5% of Americans agreeing that political violence is at least sometimes justifiable “in general” (Wintemute et al 2022). Specific situations that Americans indicated violence might be at least sometimes justified included:

- 38.0% “to oppose the government when it tries to take private land for public purposes”

- 36.2% “to prevent discrimination based on race or ethnicity”

- 24.8% “to stop an election from being stolen”

- 24.2% “to preserve an American way of life based on Western European traditions”

- 18.8% “to oppose the government when it does not share my beliefs”

- 11.6% “to return Donald Trump to the presidency this year”

- 7.3% “to stop people who do not share my beliefs from voting”

In one summary of the study, lead researcher Garen Wintemute said “We expected the findings to be concerning, but these exceeded our worst expectations,” indicating something had changed in Americans’ propensity for ideological violence. Elsewhere he was more optimistic, saying “It is important to emphasize that these findings also provide firm ground for hope. A large majority of respondents rejected political violence altogether, whether generally or in support of any single specific objective.”

Further, there was a gap between agreeing that violence was theoretically justified versus people admitting that they would be personally likely to commit violence. A small minority (4%) thought it at least somewhat likely that “I will shoot someone with a gun” in the next few years to advance a political objective. However, if this percentage is accurate, Wintemute noted that this was equivalent to about 10 million American adults agreeing that they are likely to shoot someone in the near future (versus 244 million adults who were not). Your level of optimism for our future may partly depend on which of these facts you latch onto.

Violent Fantasies

While confronting the statistical trends is important, I think we get a deeper understanding of the problem when we read people’s words, including their threats and violent fantasies. Take for example, the young man at a conservative rally in Idaho who asked the moderator: “At this point, we’re living under corporate and medical fascism. This is tyranny. When do we get to use the guns?… I mean, literally, where’s the line? How many elections are they going to steal before we kill these people?” In this man’s mind, he believed the moral foundations of oppression (“tyranny”) and fairness (stealing an election) were being violated. It doesn’t matter whether one’s perceptions are accurate; beliefs are sufficient to feel violence can be justified.

“We can no longer get rid of the tyranny by the ballots. It’s only by bullets now,” tweeted the House candidate. “Mr. President, I believe you are guilty of treason and should be publicly hung [sic]. Your son too,” tweeted the 63 year-old actor. “If we’ve got to hang a few crooked congressman, we’ll do that” said the rioter to the armed officer guarding the barricaded doors. “I prefer a Pay Per View of him (Obama) in front of the firing squad… We could make some money back from televising his death,” the NC school board candidate tweeted. He should be thrown out of a helicopter, the member of Congress insinuated about a migrant who likely beat a police officer. “Human sacrifices… Permitable (sic) but only for the corrupt rapists, pedophiles, murderers, politicians, judges,” penned the arrested brothers. “KILL ALL GAYS,” read the hacked electronic Florida traffic sign, on International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia. “The same way we’re very comfortable accepting that Nazis don’t deserve to live, fascists don’t deserve to live, racists don’t deserve to live, Zionists, they shouldn’t live in this world,” said the (banned from campus) university student. “If (election official) Stephen Richer walked in this room, I would lynch him,” the Arizona Republican party committee member told the crowd. “Trump, we want actual revenge on democrats. Meaning, we want you to hold a public execution of pelosi aoc schumer etc. And if you dont do it, the citizenry will. We’re not voting in another rigged election. Start up the firing squads, mow down these commies, and lets take america back!” wrote the 37 year-old man on Facebook. A Buffalo, NY school board member told a local media outlet that he wished Obama would die from mad cow disease and that his White House advisor Valerie Jarrett would be decapitated in prison. On another occasion, this same person told an interviewer that Attorney General Merrick Garland should be executed. And in yet another incident he was more direct, emailing his colleague (and fellow party member) “You should be hung for treason” for not supporting Trump’s presidential ambitions. There are other more elaborate forms of violent fantasies, including Rep. Paul Gosar posting an animation of him killing and attacking his Democratic colleagues (for he was censured), as well as a graphic video shown at President Trump’s Doral resort depicting him shooting political opponents and members of the media. Lastly, at a Trump rally in Pennsylvania one speaker showed a graphic showing the “angel of death” coming for Democrats, journalists, wealthy elite, and a few Republicans deemed insufficiently loyal.

Of course, fantasies can transform into direct threats.

“I’m going to murder her; I’m going to shoot her in the (expletive) head and kill her, OK…Tell the FBI,” said the 34 year-old man over the phone to Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene’s office. “I’m right behind him now. I’m going to shoot him in the head. I’m going to do it now. Are you ready?” said the 54 year-old Utah man to Rep Jerry Nadler’s office. “I’m gonna bash your mother fucking fucking head in with a bat until your brains are splattered across the fucking wall,” said the voicemail meant for Rep. George Santos. “I hope someone cuts that motherfucker’s throat from ear to ear. Cut his fucking head off. Swalwell’s a worthless piece of shit. Cut his wife’s head off. Cut his kids’ heads off,” said the 72 year-old man on a voicemail left for Rep. Eric Swalwell.

.

These are all realities we need to confront. Not everyone will act on such sentiments, fantasies, and threats, but they are deeply held beliefs (rightly or wrongly), they trigger powerful moral emotions. They are currently widespread enough that they will inexorably lead to people being physically harmed.

It probably doesn’t help the current situation that there are few prominent voices of principled nonviolence today. There is no equivalent to MLK, Gandhi, Cesar Chavez, or John Hume. Instead, the fires of outrage are regularly stoked, leaving a specter of violence hanging over us. And it probably doesn’t help when prominent politicians not so subtly threaten mass violence by praising their followers for being “Locked and LOADED” and willing to physically fight on their behalf.

Yet here we are.

.

References

Decety J, Porges EC. Imagining being the agent of actions that carry different moral consequences: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2011 Sep 1;49(11):2994-3001. Link

Wintemute GJ, Robinson S, Crawford A, Schleimer JP, Barnhorst A, Chaplin V, Tancredi D, Tomsich EA, Pear VA. Views of American democracy and society and support for political violence: First report from a nationwide population-representative survey. MedRxiv. 2022 Jul 19:2022-07. Link

Workman CI, Yoder KJ, Decety J. The dark side of morality–Neural mechanisms underpinning moral convictions and support for violence. AJOB neuroscience. 2020 Oct 1;11(4):269-84. Link

More examples:

Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson at NC church meeting: “Some folks need killing”

Georgia teacher allegedly threatens to cut off student’s head in Israeli flag dispute

Pingback: Civil War Counter – Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Pingback: Trump: 21st Century Demagogue – Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.