“Because of the values we place on sexuality in life, because of the terrible taboos which surround it, the endless lies, the forlorn wishes, the sad fantasies we wind around it like gauze about a wound (whether these things are due to the way we are brought up, or are the result of something graver – an unalterable quality in our nature), everyone’s likeliest area of psychological weakness is somewhere in the sexual.” — William Gass

With the World Cup in full swing, several light-hearted stories have circulated about which countries have restrictions against sex while their teams are still in contention. Elizabeth Abbott, in her 1999 book “A History of Celibacy” noted that there are several reasons that people have engaged in celibacy over time — including for asceticism, as clergy, to preserve virginity, as a result of coercion (ex. eunuchs), etc. She spent much of the book on several interesting historical figures, including the life of Gandhi and his own views on desire and celibacy.

He wedded very young (age 13), the result of an arranged childhood marriage. At 19 he left India, alone, to study law in England for three years, and he vowed to his wife and mother to shun alcohol, women, and meat (he was a strict vegetarian) while he was away. According to Elizabeth Abbott (1999), one source of strength for Gandhi was the following passage from the ancient Bhagavad Gita.

Bhagavad Gita:

If one ponders on objects of the senses there springs

Attraction; from attraction grows desire

Desire flames to fierce passion, passion breeds

Recklessness; then the memory – all betrayed –

Lets noble purpose go, and saps the mind,

Till purpose, mind, and man are all undone.

This reminded me, somewhat loosely, of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129:

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action: and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust;

Enjoyed no sooner but despised straight;

Past reason hunted; and no sooner had,

Past reason hated, as a swallowed bait,

On purpose laid to make the taker mad.

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind a dream.

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

And then finally the modern, less eloquent, version. (Note: mixing the Gita with pop songs could be the next Kim Kierkegaardashian).

Pink “Try” (2012):

Where there is desire there is gonna be a flame;

Where there is a flame someone’s bound to get burned.

There is a serious lesson in here somewhere, which I could probably articulate better if I had more time to think about it, or if I was smarter. Perhaps it’s along the lines of plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, that people are people, and have long held ambivalent views of desire. As Shakespeare wrote, it contains elements of both heaven and hell. At various times, sexual desire — and being perceived as desirable — can be a source of connection and intimacy, pleasure, social status (within reason), self-esteem, etc. (I wrote more on the many functions of sex here). But desire also has the potential to be disruptive and even harmful.

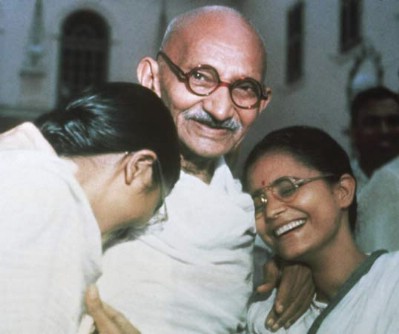

Gandhi with his grand-nieces. Source.

Gandhi’s views were affected not only by religious teachings and his own idiosyncratic, evolving philosophy on self-discipline, but also by personal events. His father, who had been ill, died while Gandhi was being intimate with his wife, Kasturbai. According to Abbott, Gandhi blamed himself and his desires for not being present at the moment of his father’s passing, and for their baby being stillborn, months later. He later took a vow of celibacy (brahmacharya), writing:

“as long as I looked upon my wife carnally, we had no real understanding. Our love did not reach a higher plane. There was affection between us always, but we came closer and closer the more we, or rather I, became restrained…The moment I bade goodbye to a life of carnal pleasure, our whole relationship became spiritual. Lust died and love reigned instead.”

I don’t know Kasturbai’s thoughts on this. Gandhi wrote that he did not consult her before taking the vow, but he also claimed that she did not object. Maybe. Like Freud, he felt that ‘civilization’ rested on individual restraint, and he took this to an extreme degree. His view on sex was that it was “a fine and noble thing” but that it was only to be used for reproduction; “any other use of it is a sin against God and humanity.”

In his pursuit of self-mastery and what he saw as “experiments with truth,” he felt that lust needed to be controlled “in thought, word, and deed.” However, Gandhi being human, the latter two seemed easier to control than the first, and that it was never easy:

“Even when I am past fifty-six years, I realize how hard a thing it is. Every day I realize more and more that it is like walking on the sword’s edge, and I see every moment the necessity for eternal vigilance.”

However, his ‘experiments’ may have created collateral damage. To Gandhi, running away from temptation was unacceptable, because that would have been the easy way out. Instead, he courted it in order to test his will. But Abbott wrote that in his own way, Gandhi was a “brahmacharya-style womanizer,” with an “ashram harem,” and that several women became casualties of his suppressed desires. He often bathed with, and entered into bed with, naked young women (several of whom may have been in their teens). He did not see this as problematic. Instead, he boasted that “he had resisted temptation to make love with thousands of women who had lusted after him. God had saved the women and Gandhi, too” (Abbott, p. 224-5). In short, he was the anti-Wilt Chamberlain.

With his status as the Mahatma (‘great soul’), several women fell in love with Gandhi, and Abbott noted that this created jealousies and built tensions, setting “the ashram’s emotional climate at boiling pitch.” So Gandhi’s beliefs and actions were not harmless, and one has to consider whether Gandhi abused his status and objectified women in a different way, by using them as part of his “experiments.” Supposedly, Nehru called Gandhi’s views on celibacy “abnormal and unnatural”.

What to make of all this? Perhaps it’s that abstaining during a World Cup is one thing; it’s quite another to renounce desire altogether, even for a mahatma. Evolutionarily speaking, desire serves several functions (as mentioned above), but these are to be expressed within culturally sanctioned parameters. Another thing to take away is that ideas matter. Across cultures, there are a wide range of views about what constitutes healthy sexuality. Gandhi’s views were at one extreme, and at either end there will probably be casualties. Too much sex, or too little. It’s a trap. Perhaps the other bit of ancient wisdom that would fit here would be to find “the middle path.”

References

Abbott E. 1999. A History of Celibacy: From Athena to Elizabeth I, Leonardo da Vinci, Florence Nighhtingale, Gandhi, & Cher. Scribner: New York. Link.

Gandhi MK. 1980. All Men Are Brothers: Autobiographical Reflections. Continuum: New York. Link

Gass W. 1976. On Being Blue: A Philosophical Inquiry. New York Review of Books. Link

I guess this one didn’t resonate.

Or maybe it resonated all too soundly?

The tensions in Gandhi’s sex life remind me somewhat of Baruya sexual practice (or at least of normative Baruya sexual practice). Role expectations, some of which I think it fair to say that many/most Westerners would frown upon, are confined to distinct stages of a man’s life: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1463499603003002004.

Great example. The power of culture! I’ve been trying to figure out the big picture. Right now, the best I can come up with is that lust is instinctive, but it is developed (a) within the individual’s biology (and will therefore vary among individuals) and (b) the individual will internalize cultural messages about the ideal way those desires should be expressed. Of course, individuals don’t have to choose the path that’s given to them by their culture.

The Gandhi example was interesting to me because here was a person often associated with supreme self-control. I’ve actually long admired him. His writings show lots of introspection and empathy, even if they’re grounded in a theological background that the scientist in me can never fully agree with. Yet in the area of desire he seemed to really struggle, and in trying to overcome desire he may have harmed many people emotionally in unintended ways.

His courting of temptation seems a bit masochistic, from which a sort of sexual pleasure could be derived. I’ve heard that the more effort you put against an idea/object/person, the more weight you give it.

Maybe you’re right. Perhaps it’s like that old saw “try not to think of a pink elephant.”

Pingback: Around the Web Digest: Week of June 22 | Savage Minds

Pingback: 2014 in Review | Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Pingback: Sex Really Is Dangerous (and Other Adjectives) | Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Pingback: Part 1. Humans are (Blank) -ogamous | Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.

Pingback: Wrapping up the (Blank)-ogamous Series – Patrick F. Clarkin, Ph.D.